This is chapter 1 of The Information Class, a tract for the times that seeks to understand and defend class stratification in America and make it serve the common good. See the overview and publication schedule here.

Why did Americans make such a bad choice in 2024?

For one thing, good decisions depend on good information, and the median voter doesn't know much. But the median voter has always been rationally ignorant, and the American people never made such a terrible choice before. So again: why? Why now?

What's different is that in the past, there was deference, to establishment politicians, to elite media, and to academics and universities. Now that has broken down. Instead, voters have become pawns of anger and misinformation, abandoning norms and traditions and surrendering to demagogues, letting the republic be demonized as the “deep state” and the rule of law as “lawfare,” disbelieving what they read, and striking blindly in the dark against the classes and institutions whose routines and labors make their freedom and high living standards possible. The internet is a big factor. It has scrambled the discourse, decentralizing and democratizing it so that new voices get heard and older authorities get eclipsed.

I mentioned the word “classes” there with deliberate casualness, meaning merely, types of people. That's a legitimate use of it.

But from now on, I'll be investing the word “class” with more definite content, taking up a long tradition associated with the name of Marx, though it's much older. “Class” can be used loosely to mean “category.” But there is also an important social phenomenon that goes by the name of “class,” meaning that people within a society are sorted into a few recognizable types, differing across several dimensions from manners to education to occupational propensities, with the differentiation beginning partly at birth, although class boundaries are usually somewhat porous.

If we use “class” in this sense, is it still true that the paranoid, conspiracy-minded, cynical, disillusioned, angry, nihilistic populists are striking blindly against the classes that sustain the institutions of freedom? Are there classes in America? Wasn't America supposed to be a “classless society?”

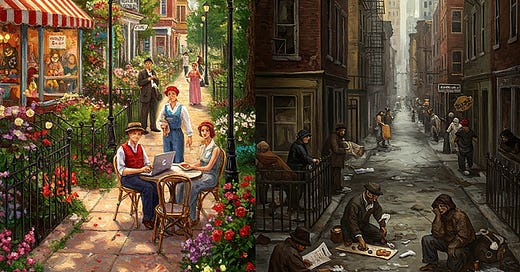

Yes, it was. That was a point of pride for a long time. There's the rub. In the past, elected officials and bureaucrats and judges felt less distinctive. They were more successful than most, but they sprang from and mingled with everybody else. They weren't a separate class. And that's why this moment is so dangerous: America has become a class-stratified society, but we refuse to accept that, to embrace it, and to give it legitimacy. Populists are angry at the people who run things because they're a different kind of people, a different class, and Americans aren't used to being governed by people of a different class from themselves.

Most leaders were always more educated and wealthier than average, of course. But the social gulf in values and lifestyles wasn't so large. I think in the past, more people looked at elites and felt they could have achieved that, if they'd worked harder and gotten a few lucky breaks. Now the feeling is: who are those people? It goes both ways. Certainly, I feel that way about MAGA voters. My imagination can't bridge the gulf to penetrate the mentality that would make them act that way. Ancient Greek philosophers and medieval knights, or Russian aristocrats in War and Peace, I can understand and sympathize with. MAGA voters are as alien as the Huns attacking Rome. I get the sense that they feel a somewhat similar sense of alienation from my class. Who are these people? they probably keep asking themselves about us. Where did they come from?

Again, a generation ago, Americans hadn't sorted themselves into classes so much, and people saw the politicians and bureaucrats and judges as people like themselves. Everyone was “middle class,” and there was more of a homogeneous national culture. But the people who have college degrees and work with their minds using computers have become more insular and distinctive, ensconced in the bubble of a new pursuit of excellence, and Americans who are stuck in the rut of an older kind of normalcy, or worse, Americans whose lives, communities and traditions have been broken by the Sexual Revolution, cannot understand us. Americans’ rulers have become strangers to them, and they don't understand why. That has given rise to a feverish atmosphere that only awaited the right spark to blaze out in a new kind of toxic identity politics of the left-behind. A certain iconoclastic, obscene, hedonistic, narcissistic, megalomaniacal business and media personality became that spark.

The role of the internet in this will be repeatedly touched on in this book without being fully addressed. It has been the liberation and the empowerment of much that is good and much that is bad, of unprecedented availability of history's heritage of genius from every smartphone, of a mass thriving of philosophy through a million threads on Facebook and X, but also of the forces of darkness, of labyrinthine, frantic phantom grievances, of racism, of rape fantasies, of conspiracy theories, of envy and hate. It is steadily shrinking the market share of old-fashioned journalism with its spirit of epistemic and civic responsibility. It has made public discourse far more participatory, for better and especially, of late, for worse. For the information class, the internet is, in different aspects, both the lance in our hand and the dragon we have to slay. Online flash mobs are howling at the gate to destroy everything civilization has built, but also, the internet has made possible whole new forms of the pursuit of excellence, and of more authentic community. It's an indispensable component of our identity as the information class.

In the face of the populist threat, do we– we of the information class– dare to say, “We’re smarter than you, so for your own good, you should calm down and let us run things?” Do we dare to acknowledge class stratification, and not apologize for it but defend it?

Many people of my class surely feel, with a timidity that is often mistaken for humility, that such “arrogance” is what got us here, and now we must avoid it, and eschew pretensions of superiority. I would reply that we have a duty to tell the truth.

But I also want to change the subject.

Armchair political strategy is of limited value. Navigating the serendipity and compromises of obtaining power and wielding it for good needs to be done in the thick of the action and in real time. I’m not in a position to help much with that. So interested of advice about coalition politics or electoral tactics, all I have to offer is moral self-help advice to the information class itself.

I think one key to saving the republic, civil peace and the rule of law will be to legitimize class stratification, to stop fighting it, to recognize that it can be a force for good, and to make it a force for good. There is no equality of opportunity. There can be noblesse oblige. The left-behind, the class prone to the appeal of populism, needs to get used to the reality that they're now largely ruled by strangers, or at any rate by a different class of people. It must be so, because we alone have the skills. But life under our leadership can be pretty good, if they'll accept the gift.

We don't need to be strangers. They can get to know us better. The classes can't be merged, but they can achieve more mutual understanding. The mere recognition of class stratification might be an important step in the right direction. They might understand us better if they didn't have lingering expectations that we'll be like them, if they looked for us to have different habits, values, motivations, pastimes and principles than themselves. But mostly, we need to give them reasons to admire us. The challenge that the populism-prone classes will need to overcome is to choose to trust the good, civilized, truth-based order that rule by the information class offers them, and to reject the demagogic, chaotic empire of lies that is the alternative. We can make that easier by acquiring enough charismatic virtue that it's fun to follow us. And we'd better do it fast.

Historically, class stratification is normal. I'll show why in the argument below, but in a nutshell, people like to marry people like themselves and give their children a headstart in life to attain careers like their own. That leads to class stratification. Mid 20th-century America was an exception, for good and bad reasons and with good and bad effects, but its classlessness was unsustainable. As America reverts to historic normalcy, nostalgia for a past time that's out of reach is a destructive force. The information class should lead the way to a different kind of future. Class stratification needn't be a disaster, it can be an opportunity, the thin end of the wedge of progress. Our class stratification can serve the common good if the ruling information class leads with virtue.