The Benedict Option

When Rod Dreher’s book The Benedict Option finally came out in 2017, I was glad someone had finally written it, though I wasn't sure I was glad it had been him. I had been already describing my own life choices as “Benedict Option” for years before the book was published. It was an idea whose time had come, a necessary idea, a call that many were hearing, and that needed to be articulated. But many never heard that call, and never understood what the “Benedict Option” meant. And Dreher's book, excellent in many ways, jumbled the idea with other pet causes of Dreher's in a way that misled some readers about its motive and meaning. And anyway, the book was really written for people who had felt the Benedict Option call already, not for unsympathetic outsiders. So many just missed the point. This post, therefore, is another attempt to explain the Benedict Option. Relative to Dreher, it's updated and the scope is a little different, and it includes my personal story. But I'm not trying to break all that much new ground here.

A secondary purpose is so that I can stop recommending Dreher's book to people quite so often, since I actually take strong exception to some things about the book. I'd like to redirect some of the traffic that I send to Dreher back to this post instead.

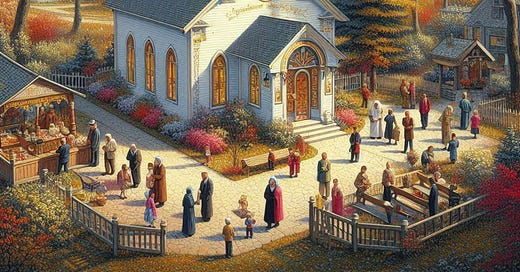

The Benedict Option is part of the broader call of the Christian counterculture. It's a way to join forces to meet more of the need for community among those whose Christian integrity requires them to withdraw from “the world,” in the old moralistic sense of that term, in various ways and degrees. It's an exciting call, a sacrifice but also an adventure, wholesome and innocent, though it often looks irresponsible to those who don't understand it. It's a way of turning one's back on a tainted mainstream culture, putting the search for Christian community and integrity first, and often kind of letting the chips fall where they may as far as one's personal finance and career path are concerned. Sometimes the Benedict Option means burning one's bridges.

One of the projects I've been pursuing through some of the post here, which I like to call “The Ethos of Chivalry,” is deliberately alternative to the Benedict Option. See “The Author as a Case Study of the Educated Elite,” “Alasdair MacIntyre and the Lost Tradition of the Virtues,” “The Age of Chivalry” and “After Chivalry.” In the Dark Ages metaphor, the Benedict Option emulates the monks, whereas my advocacy of a renewed ethos of chivalry would be a call to emulate the knights. The Benedict Option is not alternative to the ethos of chivalry in the sense that if one is right, the other has to be wrong. There's room for both “monks” and “knights” in the world. But at the individual level, they do seem largely alternative. To be a “knight,” you have to mingle in the courts of this world, show off your prowess and pursue fame. To be a “monk,” you need to leave behind the courts of this world and silence the appetite for fame. The Benedict Option is deeply at odds with the quest for worldly advancement and success.

In spite of the tensions, I have a foot in both worlds, and I often feel, at the risk of sounding a little vainglorious, like a knight hiding out among the monks.

Interestingly, the most prominent contemporary expositors and advocates of the Benedict Option, MacIntyre and Dreher, aren't and never were really practitioners of it. In a sense, they probably couldn't be, if they were to have the impact that they did. They only had enough fame and clout, and enough of opportunity to pursue specialized excellence to write their compelling books, because they were highly involved in the very worldly occupations of academia and punditry, respectively. There’s a mild irony in that the influence they have achieved is a convenient proof of concept for why some people are justified in not practicing the Benedict Option that they advocate. If all Benedict Option sympathizers were Benedict Option practitioners, none would have been in the thick of the public square enough to spread the word about the Benedict Option.

Having mentioned monks, I had better put in an important disclaimer quickly. Clearly, the Benedict Option has a monastic inspiration. And clearly, in that most full and rigorous form of the Benedict Option, namely, actual monasticism with vows of poverty, chastity and obedience, it represents something very clearly distinguished as an alternative to the world and mainstream society. But advocates of the Benedict Option like MacIntyre and Dreher do not seem to want to limit the reach of the ethos and lifestyle they advocate to those willing to take full-fledged vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. They think married people with families can meaningfully emulate the monks. There's plenty of history behind this idea, and the long tradition of the Church holding up monastic saints as models for lay Christians to admire certainly supports it. But I think there's also a risk of forgetting that the peculiar stability and purposiveness of monasticism, and the intensity of prayer and penitence that it can foster, is tied up with chastity and can't really be replicated by people who are all tangled up in the bustle and trouble of raising a family. We shouldn't expect lay versions of the Benedict Option to be as well-defined and potent as the real monastic experience.

Still, it's an important movement with a lot to offer, many people are pursuing it, and it promises to bear much wholesome fruit in the years ahead. I'll first explain my personal experience with it, and then abstract some principles by which that experience can be generalized.

My Benedict Option Adventure

I am a member of the Eastern Orthodox parish of Saint Alexander Nevsky in Richmond, Maine, and I strongly hope that I will be until the day I die. I've had to move away once under economic duress, and only the rise of telework, with a little help from home price appreciation, has made me feel fairly confident that it won't happen again. But, as God wills. As long as I can feed my family, and keep a roof over our heads, we plan to stay put. I wouldn't be enticed by a million-dollar salary in New York or San Francisco, or by a prestigious professorship or think tank job somewhere else. All I ask for in life is the services at Saint Alexander Nevsky church, the people God has given me as friends and family, and the splendid seasons of central Maine.

I wrote about it in my book of poetry, “The Rustic: Songs of Maine,” or on Substack here, trying to capture the wonder and beauty and innocence of our lives here. Some of the poems are fictionalized, mingling our life experiences with a mythic ideal of the Benedict Option. My short novel for kids, Schiller: The Monks’ Goat (also posted to Substack) also depicts the Benedict Option through a story: the monastery is inspired by Jordanville monastery in upstate New York. I'm contented. I feel very blessed.

On second thought, I actually might be enticed by a million-dollar salary in New York or San Francisco, but if I took it, I'd do it for the community. Concretely, I'd probably save the money to start an Orthodox school. Education is a pain point for our community at the moment. Most parents homeschool, and would have serious moral qualms about sending their children to public school, what with the way the culture is going and all that. But homeschooling is difficult, and some struggle at it. We've recently had some very reluctant departures from the parish by people moving to places where there are Orthodox schools that their children could attend. There's an unsettlingly experimental quality to all the educational activities in the parish. In a word, we don't know what we're doing.

And that puzzlement is just the tip of the iceberg, for most of the parishioners seem to be here as a result of some radical discontinuity in their lives, and we're not living the way we know from how we were raised. We're traditional in theology and morals, but experimental in lifestyle. There are a lot of dreams invested in the Saint Alexander Nevsky parish. It's a dream come true for a lot of people, in different ways, and probably in most cases a dream come true that fell short. We're building something, but we don't know what. And our kids are along for the ride, willy-nilly. My kids’ childhoods are a lot different than mine was. I'm endlessly haunted by premonitions that I'll feel guilty later for some opportunity that I had but didn't give them. And yet, they're happy, and remarkably innocent. That's worth a lot. My worries are frequent, but not that serious. Faith in Christ is worth more than all the world's money or fame or success or pleasure, and this seems like a good place to inculcate that.

Lately, in addition to some education-driven departures, we've also lost some members for the rather happy reason that so many new Orthodox churches are springing up around Maine. Some parishioners have moved to the new parishes, either to strengthen and help build them up, or for a shorter drive time, or some combination of these and other reasons. That has left us short of choir singers and Sunday school teachers, organizers of cooks for the shared meal after church, and so on. At the same time, the church has gotten crowded on Sunday mornings as new people come in. There's talk of needing a new church, but we have no idea how to finance that. And we may never need one after all, if growing churches in nearby towns siphon off enough of our own growth.

The parish hall where we eat “trapeza” (a post-Liturgy meal) together after services is even more crowded than the church. Some people don't attend because there isn't room. That's a rather urgent need, really, and when we bought twenty acres of land out in the country last year, for a cemetery, there was talk of building a new parish hall there, too. But things move slowly, by painstaking near-consensus achieved through long, rambling conversations that take place at infrequent meetings. Sometimes people get frustrated that they're not involved, while other people are overburdened with duties. Community organizing is a messy, clumsy, rather inefficient business. But we all get along. We love each other.

We've had a lot of male converts in particular, recently, creating a severe gender imbalance among the young singles. Who will all these young men marry? Why aren't there more women converts? Then again, are these young men husband material, anyway? They're pious, nice, honorable guys in the prime of life, but there's a certain mingling of bachelor independence with Christian integrity that might not lend itself to holding jobs that have enough upward income mobility to support the stable middle-class lifestyles that a lot of girls want. But maybe they'll find girls who are willing to be poor, or maybe they'll turn on a dime and make more money when there's a girl to do it for. Who knows?

What the parish will look like in twenty years is anyone's guess. Except that it will be faithful to Christian truth. We're all dead set on that. We know that the Saint Alexander Nevsky parish community won't succumb to the latest progressive moral fashions. We will keep on teaching the morals and theology that the Orthodox Church has taught for 2,000 years. We know the Liturgy will remain the same, word for word, and the feasts and fasts will fall on the appointed days year after year. Day to day, we're experimenting, unsure what to do, planning and not following through. But we share a more fundamental certitude and consistency.

Our doors are open! You're welcome to join us. Just show up on any Sunday morning at 9AM at 15 Church St, Richmond, ME 04357, and walk in. We'll be there. There will be someone chanting, and some people, though not everyone yet, venerating icons and praying. People probably won't come up and introduce themselves at this stage, since the church is supposed to be quiet, although they might do so, in whispers. Then the Liturgy will begin, a long, solemn drama, with the lights on, priests vested, the choir singing in full harmony, and thousands of ancient words of wisdom will flow, and the Body and Blood of Christ will be distributed to the people. If you're new to Orthodoxy, you won't really understand what's going on, but you'll probably be moved by the golden solemnity of it, a kind of touch of heaven that forms a halo around everything. And then, after the prayers of thanksgiving, everyone will drift out, and we'll linger a while in the courtyard talking, and if you stand around looking like you'd like to talk, someone is likely to greet you and introduce themselves. No promises. There's been so much growth lately that we don't know all one another's names, so we might not realize you're a visitor! But we try to greet visitors. Feel free to accost us and introduce yourself.

After that, we’ll walk just down the road to the parish hall for “trapeza,” the post-Liturgy meal, and definitely feel free to join us for that, and get to know us better. Everyone will be fed for free (requested donations from members only). You can wax as eloquent, or express yourself as haltingly and clumsily, as you like. Tell us all your troubles. We know the secret of God's healing. Ask your questions. We have answers. You have friends here if you want them.

But remember: if you've absorbed a lot of fashionable moral opinions, you'll need to leave them at the door. There's no inquisition, but you'll know you don't fit in, and all the smiles won't please you. You'll feel uncomfortable, you'll hear things you don't understand and that make you nervous, and you probably won't come back. For we believe what Christians have believed for 2,000 years. We don’t move with the times. We have no use for the latest woke rubbish. For example, we know that marriage is between a man and a woman. The ancient texts don't say so, because that particular error hasn't been around long enough for the refutation of it to be worked into them. We don't hear about it much in the homilies, either. Why state the obvious? There are more important things to do. But we know. The moral fads don't stand a chance among us.

Sometimes we help each other out.

A few years ago, a young couple in the parish with a kid or two was staying with an older homeowning couple in the parish. The older couple’s situation changed, and they needed to sell their house. The young couple was suddenly about to be homeless. They were ready to buy, but that takes time. Fortunately, another family was living out of state for a job and had a vacant house. They let the young couple stay there, free of charge, until they bought a place a few months later.

There was another case involving a vacant house and an out-of-state job, but that time the family that needed housing moved to Saint Alexander Nevsky parish out of the blue, on some kind of spiritual impulse. I've known them for years and they're friends of mine, but there's still something mysterious about that move. They had no connections in Maine at all, except a little hearsay and one encounter with the priest. They left everything to come here, after finding a local job that wasn't very good and that soon fell through. The vacant house gave them a place to land, and no rent was charged during the unemployment spell. But soon they sort of landed on their feet, albeit the house they bought was very small and dilapidated. Now, several years later, some of the young men in the parish are building them a new one. I assume they're paying for that somehow. I don't know. Perhaps not.

That family's coming here was striking, because it seems it could have no possible motive other than the desire to live amidst a wholesome Christian community of strong faith and pious practice. It makes no sense apart from that. It's a kind of rarefied, lucid example of the Benedict Option. Another family’s move to the area is similar except that it involved no economic sacrifice since the husband has a good telework job, but they too had no motive for moving except to join a church community with an appealing reputation.

It's nice, by the way, that we have a lot of construction muscle in this parish. Volunteers recently built a small extension of the church.

Like many parishes, we have a disabled lady who needed rides to church from the parishioners every week until she recently moved closer. People step up to volunteer. Another woman came here several years back, living in a trailer, and a couple of people let her park it on their land at one time or another. She wintered here, which takes some toughness. In the end, she never quite struck root, and moved on, but we were glad to have her for a little while.

That woman had lived in Alaska. So have some others in our parish. If you’re from Boston or New York or DC, this place will seem pretty remote, but not compared to that. If I’ve got the story right, one gentleman in the parish went up there to Alaska to help a woman run away from the law, after a judge ordered her to share her kids with an ex-husband whose murderous propensities were known to her but didn't convince a judge. He stayed there for a few years, beyond the reach of civilization. He told me once about harvesting moose. One or two others have been on the wrong side of the law in one way or another sometime.

There's no class stratification at Saint Alexander Nevsky parish. Whatever honor or shame we may have won or lost in the world is nothing compared to the shame of sin and passion to which we are all prone, or the incredible honor partaking of the body and blood of Christ, which none of us deserve but all of us are given. Church is a place to take a break from class consciousness, and to partially unlearn it.

Perhaps there is class stratification of a different sort, though. Seniority matters. Lots of people come and go. We love them. But we don't trust them in the way we trust the committed. If you want to be smiled at and tell your stories, you're welcome, but if you want to volunteer to teach Sunday school, you'd better have been around for a while.

There was another time that $700 was given by one family to another family, completely unsolicited, no quid pro quos, and quietly, and that’s an interesting case because the giving family wasn't wealthy, though their business was doing pretty well, and the receiving family wasn't poor, though it had suffered a big drop in income. The receiving family had previously, in more prosperous days, done a good turn or two for other families in the parish, though never for the giving family. Perhaps the gift was meant as a kind of payback on behalf of the parish, but I don't know. I don't think they ever discussed the matter. “When you give arms, let not your left hand know what your right hand is doing” (Matthew 6:3).

My loyalty to the Saint Alexander Nevsky parish is not a matter of carefully calculated optimization. I can't prove that this is the place where my family would flourish best. I can't prove that this is the place where I can be of the most service to the kingdom of God. What I could prove, I think, or any rate make a good argument for, is that loyalty is valuable. Lots of good ideas fail through turnover. People think of something, put in some effort, make some progress, and then think of something better, and one thing follows another, but nothing lasts. It happens all the time.

In marriage, if you realize you'd be a better fit for some other person than for your spouse, never mind. Stick with your spouse all the same.

There's no warrant for being as stubborn in your loyalty to a parish as in your loyalty to a spouse, but the same principle applies to some extent. It takes a long time to get to know people. Relationships bear fruit slowly. People need anchors. They may come to rely on you, and you won't even know it. You'll never know the damage you do by being unstable. Don't get me wrong: I love rambling, travel, adventure, and I've done my share. But it's also good to put down roots.

My loyalty to Saint Alexander Nevsky parish has an almost ethnic flavor. It's my people. For better or worse. Uncritical. Stubborn. And yet it's not ethnic. It's intentional. It's chosen. But the choice has a once-and-for-all character. I don't revisit it. There's no looking back. No doubting. I'm open to the will of God to override it if He sees fit, but He'll have to make it pretty obvious and compelling, because I'm not on the lookout for signs of whether I'm doing the right thing by staying here. Some parishioners have left to be priests at other parishes, or for monastic vocations. We wish them well, God bless their paths, and praise God that our humble parish has been able to bear such glorious fruit. But for my part, I don't dream any dreams that involve leaving here. Any dream that flits through my mind had better include Saint Alexander Nevsky parish, or it will be dropped very quickly.

If you read this post and want to come join us, but it takes you ten years to save up and makes the arrangements, it's a good bet that I'll still be here. We can be friends then.

But— if you read this post and already have a parish, and this post makes you want to leave your parish in favor of Saint Alexander Nevsky, think twice, and pray long and hard. Loyalty to your parish is a good thing. Don’t be a church shopper.

As I suggested above, the kind of lived experience of the Benedict Option that I've had at Saint Alexander Nevsky church is something that its more famous champions, MacIntyre and Dreher, lack. MacIntyre arrived at the Benedict Option as a kind of theoretical conclusion at the end of a long argument. Dreher interviewed many Benedict Option practitioners for his book, but his own attempt to practice it, by moving back to his Louisiana hometown and trying to imitate his stay-at-home sister Ruthie, was a ruinous failure, as he has admitted poignantly and at great length in his own writings. I'm not criticizing either writer in saying that they write about the Benedict Option as outsiders. Again— if anything, that's necessary to the broader perspective that has enabled them to write about it with sufficient generality to establish the phenomenon. But it's a limitation, too.

Perhaps my description of the Benedict Option will strike some as simply the description of a parish, with no need to invoke a special new concept to explain it. To my mind, though, the concept of a parish and the concept of the Benedict Option are definitely distinct, even if they overlap.

Two examples of parishes that are not Benedict Option might be called (a) the “hometown parish” and (b) the “convenience parish.”

Far be it from me to judge either. They can both do wonderful work.

By the “hometown parish,” I mean a parish where most parishioners grew up there, and the typical parishioner resembles the local population. By the “convenience parish,” I mean that the parish attracts members in large part through being convenient to attend amidst their busy lives doing something else. In a hometown parish or a convenience parish, the reason most parishioners live in the area is not because of the church. If most parishioners do live in the area for the sake of participating in the parish, it's probably animated by the spirit of the Benedict Option.

The virtues and temptations of each kind of parish are a little different.

The hometown parish, I think, has become much rarer as churchgoing habits have retreated. If I feel like I know something about it, it's more from secondhand stories from my elders and from literary sources then from personal experience, though I have participated in a couple of churches that have a little of this flavor. Reverend Lovejoy’s church, in The Simpsons, is the most recent literary example that I know of. A hometown parish is relaxed, not embattled. It has all sorts of habits affectionately treasured, and memories from decades or generations before, which still feel at home. Children go to the same church as their parents and grandparents before them, and as kids they know from school. Chance meetings with fellow parishioners outside of church are unsurprising. Conformism is an important motive for attendance. That broadens the church's reach.

A hometown church fits in. It finds it easy to be civic-minded. The big temptation here is to be too comfortable in the world, too complacent and accommodating, and to go with the times. It doesn't have much spirit to defy the age. Even if it does so, compelled by conscience or just resentfully discombobulated, it struggles to do it in the right spirit, or to discern what to fight for and where to yield.

The phrase “convenience parish” probably sounds dismissive, because everyone underestimates the importance and value of convenience. I could call it an “outreach-oriented” parish or even a “missionary” parish to sound more positive, but I mean something broader. The parish to which I am most indebted, Saint John the Baptist in Washington, DC, where pious practice was blessedly intense, and half the conversations around the lunch tables seemed to have spiritual themes, is a convenience parish in my sense. It serves mostly people who live in DC for work, with the help of a convenient location. The convenience made it possible for me to drop in and discover the Orthodox faith. More generally, the wonderful virtue of convenience is that it enables lots of people to participate, or to participate more vigorously, than they could have done in a less convenient church.

But the danger is that a parish will come to value marketing over loyalty, and parishioners will treat it as a service provider rather than a community. HR sometimes uses the phrase “work-life balance” to mean that work leaves room for a personal life. One's life is split into spheres: work and personal. A similar split can take place, whereby church is one domain, a kind of hobby cum social club, which doesn't interfere with other domains, such as work and non-church friends, other hobbies and social life. A Benedict Option parish tends to be more holistic, at least aspirationally. People are “in each other's pockets” more, as I've heard it said, hiring each other and forming business partnerships. A certain limited mutual accountability for how one makes one's living arises naturally. There are fewer boundaries.

I think it's also a sign of a Benedict Option parish that people don't have local friends outside of church. Not that it's forbidden, or even considered undesirable. But one is too busy. At Saint Alexander Nevsky, there are lots of people I admire and would like to spend more time with, but it's hard to find the time and make the arrangements. I have friends in distant places with whom I interact on social media. But to try to make friends and spend significant time socially with local people who aren't in the parish is down the priority list enough that it seems unlikely to ever happen. I guess there's a little of it. We have wonderful, kind immediate neighbors who invite us sometimes.

The social self-sufficiency of the parish is part of why the unwholesome moral fads of our time have ceased to matter for me personally. I'm not likely to find myself in a social situation where someone refers to a man's “husband,” or to a biological male as “she,” and I'm forced to pretend. Almost all my social interactions are with fellow members of Saint Alexander Nevsky parish. There, even if someone did manage to err on such a point, the authority of the Church would be immediately invoked to correct them.

Work is different, and has its moral hazards. But for what it's worth, if I did find myself in a job where I was pressured to conform to woke culture, I could spread word in the parish and people would try to help. The need to have work that's consistent with one's Christian integrity is well-understood in this parish and a priority. That's why a lot of people here work below their educational rank. We have people with college and even grad school working in construction. That's not looked down on at all. It's assumed to come from a quest for personal integrity by disengaging from a wayward elite culture.

My descriptions of hometown and convenience parishes are rather vague and impressionistic, but they should suffice to give the Benedict Option distinctness. The Benedict Option is not a mere relabeling of the ordinary, general phenomenon of parish life. It's broader as well as narrower: online communities can have a Benedict Option character. Benedict Option parishes tend to be rigorous guardians of tradition, and can foster a richer sense of community and commitment than convenience parishes. They are prone to impoverishment, both economic and cultural, through relative autarky, but that's not inevitable, and I think the sheer adventure of it can spur creativity and spontaneity, combined with a more selective and intentional engagement with mainstream culture.

Benedict Option communities also face a temptation to be too countercultural, or to be countercultural in wrong or simply irrelevant ways. If you're going to reject the Sexual Revolution, why not be an antivaxxer, too? If you're already committed to a lifestyle that embodies rejection of the moral mainstream, why not be anticapitalist and credulous of conspiracy theories as well? People may self-select into Benedict Option communities based on all sorts of weird alienations, but a strong scriptural foundation and prayer life should filter out those who join for the wrong reasons pretty effectively. Some people come and then go because we turn out not to be weird enough for them, not sympathetic enough to their conspiracy theories. One sojourner among us was so obsessed with hatred of the neocons that he told me he asked for intercessory prayers from Saddam Hussein, as from a saint, and also said, if I understood him, that a jealous husband was always justified, because his jealousy was proof that his wife had done something wrong. He's not here anymore.

The Benedict Option is not a panacea, and like all ways of life in this world, it would go awry if not continually corrected by self-examination in light of the teachings of Christ, and the practice of prayer and humility. But it can be a wonderful adventure of the rediscovery of innocence, a fount of joy and renewal, an escape from loneliness and meaninglessness, a liberation. I think that many will find that if they zealously follow the road of Christian integrity, they'll find that in these times, the Benedict Option is what it will lead them to.

The Benedict Option in Ten Principles

What is the broader phenomenon exemplified by the Saint Alexander Nevsky parish? For we're not unique. Lots of travelers come to visit, many from other Orthodox parishes, and I often hear similar stories.

I think the best way to generalize from something is to articulate its defining principles. There is a long history from which to learn these principles, since the Benedict Option is a kind of watered-down version of monasticism, and monasticism has been around for over fifteen hundred years. I think it's a widespread pattern, notably in Russia but elsewhere as well, that monastics were often the pioneers, who fled the world only for the world to follow, and that's how Christian civilization spread and colonized the land. Years ago, in grad school, I wrote an article called “The Economics of Monasticism,” in which I first reviewed the history of monasticism, extracted a few patterns from it, and then developed a theory which I thought explained it. The theory is too technical to present here, but I'll be channeling that, as well as biblical and pious reading, and personal experience.

The argument will seem to prove too much, for the step-by-step movement from truth to truth may suggest that everyone should live the Benedict Option. In fact, though, I think there are important off-ramps, and the non-Benedict Option lifestyles can be justified for Christians. I'll circle back to that.

1. Most people can only flourish in community. To understand the Benedict Option, start with this: most people can only flourish in community. They can't be happy all by themselves. They'd get lonely, and they wouldn't have much fun. They'd miss opportunities for wisdom, help in times of need, and above all, love. There may be saintly hermits who can go off and live by themselves in the wilderness praising God, and be perfectly happy. In fact, they're important to the Benedict Option, for they’re sometimes the catalyst, the focal point around which Benedict Option communities gather. But they are very few. The need for community has both an economic and a moral aspect. People's material well-being involves a lot of interdependence with others. But we also need to love and learn from others. We need community as the stage on which we enact our lives.

2. Many good things are the better for sharing. Focusing for a moment on the economic side, sharing is good. Many goods can be shared, in the sense that they can be used without being used up, or used by multiple people at the same time. A movie can be watched by many people at once. Many people can sit in a beautiful garden at the same time. Book reading is typically more private, though books can be read aloud to a group. But a library is a shareable resource since it's nice to have access to far more books than you're reading at any given time. Food is private, in the sense that you and I cannot both eat the same apple, but cooking is somewhat shareable, since I can often cook a meal for ten without too much more effort then it would take to cook a meal for myself alone. A car trip is private in that it can only go one route at a time, but people can ride together if they're going to the same place, and the same car may serve a whole household of intermittent drivers without too much inconvenience to any of them. In general, sharing promotes efficiency, since the same resources serve more people.

Much sharing is mediated through the market, in which case we probably don't call it “sharing,” but “renting,” or in other cases, simply “buying” and “selling.” Sharing through the market vastly increases its reach, but if often involves extra transactions costs to overcome low trust. It misses out on the social pleasure of sharing, which come from the way giving and lending without repayment serve to express love. Market-mediated sharing also often brings us into contact with people we would rather not form communities with. When a loving community shares things, it raises material living standards and creates happiness, in ways that are not captured in GDP, while also conferring a kind of social flourishing and strengthening the community.

3. Human flourishing consists, above all, in the acquisition of virtue. Economics has a blind spot for non-market-based sharing, but there’s a more serious blind spot, too. It can’t understand the value of virtue. Happiness, flourishing, and the meaning of life depends less on what one gets and uses than on what one is and becomes. What does it profit a man to gain the whole world and lose his own soul? It's more important to happiness to be good than to have goods.

Suppose a man ends his life having achieved great wealth, power, and fame, but he is a foolish coward, lustful and gluttonous and unable to control his impulses, vain, continually unfair in his judgments and treatment of others, full of unjustified grievances against almost everyone, completely selfish and loving nothing and no one, lacking any principles and changing from day to day, and unable to conceive of any life except a continuation of his tiresome treadmill of vanity, self-indulgence, and petty resentments. At the time of writing, one such man has dominated the public square in this benighted country for a decade, and surely anyone of sense can readily agree that there can be no greater curse than to be such a man. By contrast, many Christian saints have lived in poverty and faced persecution while continually rejoicing in the Lord.

Virtue is the true wealth. In a sense, without it, nothing can do us any good, while with it, nothing can do us any harm. That, however, may be saying more than most people would admit, and it's also more than the argument needs. To carry the argument forward, it's enough to establish that the pursuit of virtue is important among life's ends, a truth that few would deny, even if it is often left out of account. People go to church partly to get instruction and encouragement in the pursuit of virtue, and that’s also an important reason to seek out the Benedict Option.

4. Virtue and community need each other. For most people, the best place to cultivate the virtues is in the midst of some sort of community. Community serves, first of all, as a source of moral role models to emulate. It's a source of moral advice and instruction as well as moral feedback. We learn right and wrong in part from what others praise and blame us for. Some virtues, such as justice and love, are inherently other-regarding. Love means loving someone else. By the same token, the virtues are indispensable to the building of community. People stick together and cooperate better if they love each other. They also need to treat each other fairly. A good community shares hope for the future and is faithful to its traditions. People are brave at need, and courageous action in a crisis is expected and encouraged. Without virtue, communities degenerate or wither.

Everything in the argument so far is applicable to the Benedict Option but not specific to it.

5. Community often corrupts, and purity and innocence are valuable. Unfortunately, community often corrupts. You may have heard of “peer pressure” as a temptation for youth, or of “social sin” that inheres in societies and stains the consciences of all their members. Yes. It's important. Sartre said “hell is other people,” which is a snarky exaggeration, but sometimes it's true. People gossip and slander. People tell dirty jokes. People form cliques that hate outgroups. People lie, and repeat one another's lies. People exploit each other.

Of course, it can be in combating these evils within one's community that opportunities to practice virtue come. But that has its limits. Sometimes it's clear that one will lose. Sometimes the ends don't justify the means. Sometimes, you just have to let people make their own mistakes, but that doesn't mean you have to stick around to suffer the consequences of their mistakes. Sometimes you have no way to effectively fight it, yet your unresisting presence will seem to condone it. Sometimes the best thing you could do is to walk away.

But where to? You need the community. It meets all kinds of needs even when it does all kinds of harm.

The Benedict option is, in varying ways and degrees, about replacing corrupt legacy communities with new ones that you'll find or found.

6. Founding new communities is difficult because there's a large initial coordination problem, and then they can fail through turnover. The essential Benedict Option impulse thus arises when the response to a corrupt mainstream community is to withdraw, and either start from scratch, or else join, a new community, where a more virtuous life can be lived.

But this is very difficult to do.

Part of the problem is economic. Division of labor, specialization and trade, and accumulated capital make huge contributions to productivity. A thick entanglement with capitalism tends to involve some social as well as economic integration, and social withdrawal usually involves economic sacrifice. The trade-off is typically impoverishment for integrity, at least in the short run. You hear fewer dirty jokes, you escape the pressure to conform to the latest moral fads, but your living standards likely fall as well.

But even more serious is the coordination problem. Let's say that you could succeed with a Benedict Option community of 100 people. That would provide the economic and moral critical mass to make livings and raise families. And let's say there are 10,000 suitable people living in various places who would prefer to live in a Benedict Option community like that, rather than where they are. It seems like a solvable problem. But somehow you have to coordinate. Where do you go, and when do you start? If you can't agree, it doesn't work. People will have their preferences, but also, they don't want to go out to a new community site and find that they're the only one, or that there are just a few. A lot might want to wait and see. Those who come may not stay, either because they realize that they didn't know their own preferences and needs, or because the community doesn't form quickly enough to be as thriving as they hoped. You might even achieve critical mass initially, then lose it through turnover.

The turnover problem is the biggest reason why secular socialist communes always fail, fast or slow, but generally in two or three generations at most.

In complete contrast, monasteries are highly durable, lasting hundreds of years. Their secret is Christian prayer. That activity has some unique properties that make it capable of solving the turnover problem and making Benedict Option communities stable.

7. Prayer, holiness and purity are enjoyed more, the more you practice them. People enjoy doing lots of different things, and one of them is prayer. Most people pray at least once a week. I can't find them now for some reason, but I remember seeing research about time use that ranked prayer and worship pretty high in people's list of most enjoyed activities. That was a bit surprising, at one level, since it is not usually undertaken for the purpose of pleasure or enjoyment. Religious people consider it a duty, as well as a means to many ends, suggest the blessings that Christians ask God for in prayer. But I know from experience and reading that prayer can bring peace to the soul, and a kind of exaltation, as well as I mood that enhances the enjoyment of other things.

Moreover, the more you do it, the better you can do it, and the more you enjoy it. That's a feature of many activities. Sometimes we call them “acquired tastes,” though the phenomenon is broader than the typical usage of that phrase. There is another term, “addiction,” which also refers to something you want more when you do it more. Of course, “acquired taste” has a positive, “addiction” a negative connotation. Is that gratuitous, or is there a real difference? I think it's real, and the difference comes from the conflict of impulse control and intentional pursuit of the good life. Acquired tastes are part of the good life. Addictions are not. We might say that prayer is an acquired taste.

And yet I almost want to call prayer an addiction nonetheless, because of the intensity of the desire for it. “As the hart panteth after the water brooks,” sings the psalmist, “so panteth my soul after thee, O God” (Psalms 42:1). People don't usually overhaul their lives, abandon other interests, become a stranger to their friends, and burn all their bridges for the sake of acquired tastes. Acquired tastes are moderately and prudently indulged. Addictions to drugs, alcohol, and pornography become all-consuming passions that turn life into hell. Prayer becomes an all-consuming passion that turns life into heaven.

I once knew a woman whose life had been hijacked by the love of prayer, which was creating distance between her and her old friends. She told me that her friends would tell her, “I like you, except for this religion thing.” But, she said, “that's the only part of me that's real.”

Many Christian saints are remembered as having lost interest in sex, food, comfortable clothes, and almost all temporal comfort or concern for the body or entertainment or social prestige, in an ecstasy of almost perpetual prayer. Sex and family formation, in particular, are hardwired to be very strong and stubborn human preferences, as our selfish genes, for the sake of their own survival, must guarantee. It is very atypical for people to voluntarily forgo them. But the one activity for the sake of which many people down the ages have voluntarily forgone sex and family for their whole lives is Christian prayer and worship, as the entire history of monasticism proves.

The prayer motive is the key to the Benedict Option. A community that can fulfill the ever growing desire for more prayer can immunize itself against the turnover problem.

8. Prayer and holiness are also better enjoyed in the company of other prayerful and holy people. The other key piece of the Benedict Option puzzle is that prayer and worship are more rewarding in the presence of holy people. Or perhaps in the absence of unholy people, which sort of comes to the same thing and sort of doesn't.

Suppose you're in a museum, about to admire your favorite painting, when you see something horrible. It's been vandalized. Something obscene has been written in orange spray paint across one corner. Can you still enjoy the painting? After all, 99% of it is unmarred. Probably not. The coherence is part of the beauty.

It's like that in a church service. One person misbehaving can spoil it, in the sense of making it impossible to pay for attention to one's prayers. The presence of one unworthy person, if present not from penitence but to scoff, could make it hard to focus.

By contrast, suppose you're touring the museum with a great, humane art critic. He might enhance your enjoyment much, even if he doesn't say a word. You can observe which paintings he stops at longest, and take your cue that here your effort of appreciation will be well rewarded. You can see what features he observes, and in what mood, and learn. All the better if he speaks, providing context or alerting you what to notice.

So in a church service, only more so. Experienced, faithful Christians can show you when to stand and when to sit, when and how to cross yourself, or to speak along with the Lord's prayer, when and how to venerate the icons, whisper explanations of what's happening. Their focus helps you focus. They can answer your questions after the service, help you interpret what you heard and your own reflections that it provoked, and add their own testimonials and spiritual experiences. And if the service makes you aspire to live a life pleasing to God, you can look to their example.

9. Benedict Option communities arise when prayer-oriented people seek each other out and form communities that enable them to replace the functions of corrupt worldly communities, and selectively disengage. And here's where we get to the heart of the Benedict Option. A Benedict Option community forms when people try to withdraw from a corrupt mainstream society and found or join a morally purer community, and that community’s coherence and sustainability arises from the appetite for prayer. People stay because they want to pray, and to pray with others, and with others who have a real love of God and belief in Christian truth, and a determination to submit their lives to Him. In short, holiness, or at least an aspiration to holiness. The more they pray, the holier they get. The holier they get, the more they want to pray. The more holiness grows in the community, the greater its advantage compared to the world as a place for prayer. The greater its advantage, the less people want to leave, and the more sacrifices they're willing to make in order to stay. Virtuous circle.

To put it in a way that's a little bit too pithy: a Benedict Option community is a half-hearted socialist commune jumbled up with a prayer junkie club.

My fellow parishioners probably wouldn't thank me for describing the parish that way. For one thing, we don't like socialism; the parish was founded by refugees from the Russian Revolution. And we have our own houses and bank accounts. But I think mainstream worldly people would find our concern for each other's economic well-being, and our willingness to help out in mildly meddlesome ways, a little odd, and a little socialistic. And again, prayer isn't really like an addiction, because it makes people better and happier, not worse and more miserable. But it does become an urgent and dominant appetite, and it is that appetite for prayer that brings us together again and again and keeps the community tight.

Actual monasteries, of course, are real full-fledged socialist communes and also completely dedicated prayer societies.

Note that I'm not describing the Benedict Option as a community of people who make sharing work because they're more virtuous than others. You might have expected that, from hints earlier in the argument. Yes, good sharing can raise living standards. But it's subject to free rider problems. Yes, virtue can help fix free rider problems. And the purpose I started out with in my case for founding new communities was the cultivation of the virtues. But I don't think pursuit of virtue clubs work. Prayer junkie clubs do. I don't fully understand why, and what I do understand would take too long to explain, except that it has something to do with the coordination hurdle being too high. Anyway, it's fact as practical as the medieval monks colonizing the wilderness or the Pilgrims found in conducive society in Massachusetts in order to be a light to the world. Religion is the only force that can found wholesome new communities.

Once you start a prayer junkie club, it can double to some extent as a pursuit of virtue club, but not to a very great extent. We're not saints and heroes at Saint Alexander Nevsky, as far as I can tell. We're pretty ordinary. And yet we do, by the grace of God, manage to sustain a nice friendly sociability combined with a remarkable exclusion of worldly corruptions and moral fads. It's a refuge from tainted times.

10. There is a cycle by which prayer fosters virtue, which fosters prosperity, which attracts worldlings, which dilutes prayer, and makes people want to withdraw again into new communities more focused on prayer. The ultimate irony of the Benedict Option is it it tends to be the victim of its own success. Prayer breeds virtue, virtue breeds prosperity, and prosperity crowds out the appetite for prayer. The history of monasticism is full of this pattern, the best case in point being the Cistercians, who succeeded from the Benedictines because they had become prosperous in worldly in pursuit of a pure life of work and prayer in the wilderness, and consequently colonized new lands and eventually became, if anything, even more prosperous. At Saint Alexander Nevsky, we get a glimpse of this regularly when some pious young person who came to most even of the weekday services gets a job and has to cut church attendance a lot because of work shifts. In one of Jesus’s parables, God is represented as a bridegroom who has invited many friends to his wedding, but they all make excuses and don't come, so he gets angry. The excuses all have to do with worldly prosperity. One has married a wife. One has bought a team of oxen. Another has bought lands. The excuses don't seem very good. Why can't he leave his wife for a few hours to go to the wedding, or better yet, bring her along? Does the new team of oxen really have to be tested right then? But that's how it often is with worldly prosperity. It seems so important. It seizes your attention.

When I first came to Saint Alexander Nevsky, the people struck me as, on average, prayerful but rather poor and improvident. I wouldn't say that now, partly because my own expectations have been somewhat reset. But also, a lot of individual families have moved up in the world, and some of the incoming families are on the better-off side. Some have gone the other way, too, but I think the trend is towards becoming more middle-class. There's a lot of accident in this, related to both individual life stories and the regional macroeconomy. But I think an important part of it also has to do with the nature of the Benedict Option.

I don't want to go all prosperity gospel here. I don't think virtue particularly tends to promote economic prosperity for individuals. It often does. Virtue can make you work hard, make people trust you, make you abstain from superfluous consumption, and so forth. But virtue is just as likely to make you sacrifice prosperity. It makes you deal honestly when you could have gotten an unfair advantage. It makes you give away to the needy, and volunteer your time to work without pay. Nor do I think prayer promotes virtue very quickly, on average. Much depends on education and life experience.

And yet prayer does leaven the soul with virtue little by little, and makes a big difference in the long run. And I think that virtue does promote the prosperity of communities, since it makes the individuals more productive and also help each other out. At Saint Alexander Nevsky, many parishioners have worked for or rented accommodations from other parishioners. We lend cars to each other, babysit and dog sit for each other, get things away to each other, give people tips about where to buy and sell and who to hire. To date, it's all a bit clumsy and irregular, and it probably falls well short of replacing the income losses that some have experienced by uprooting themselves to settle here. Collectively, we'd probably make more money if we have never heard of Saint Alexander Nevsky parish. But we're learning. Our children will be able to leverage all the practical experience and business connections, and choose their paths in formal education to compliment that. I think the odds are good that the parish will keep growing and getting more prosperous in the coming decades. And therein lies the danger.

It's a kind of dream of mine to build up a pious, active business community within Saint Alexander Nevsky such that we could provide a job and an adequate living to anyone who lost a livelihood because of their Christian integrity. It would be fun to manage such a volume of thriving projects and enterprises with people I like so much. Maybe we could also run the businesses so that our got all the Church feast days off. I've occasionally tried to stir up conversations about that among the more business-minded parishioners, but so far, it's never really gone anywhere. It wouldn't surprise me if it does get momentum sometime, and it might do a lot of good. But so much business success would also tend to attract people to the parish who were more interested in making business connections than in prayer. Our doors, as I say, are open. Everyone is welcome. But the community retains its distinctive character, and above all, a fairly prayerful focus and strong traditionalism in theology and morals, because there's not much reason to participate in the community unless you value that. Prosperity could spoil that.

So if we do prosper mightily in the coming years, I expect that some will miss the old days when we were jobless half the time and had nothing better to do than pray. And the best of us might run away to escape our worldliness, and somehow seek the holy wilderness again, to focus on prayer.

Finally: The Benedict Option is a Liberal Idea

Now for aficionados of MacIntyre and/or Dreher, the above may be disappointingly innocuous. MacIntyre and Dreher both mount sweeping condemnations of all of Western modernity, with a particular grudge against liberalism in the broadest sense. I skipped all that, but I trust my account of the Benedict Option seems relatively complete and self-contained. My case for the Benedict Option doesn't have a rejection-of-Western-modernity sized hole in it. That's not needed. So why do MacIntyre and Dreher make that their starting place?

Clickbait.

The term is anachronistic, of course, since After Virtue was published before the Internet (1984). But to lead with a shock thesis in order to get readers hooked on an argument is a tactic that precedes the internet. You might call it sensationalism, but the word “clickbait” fits the bill well.

I don't want to be too cynical. I think MacIntyre really believed in his “disquieting suggestion” that all Westerners don't know what they're talking about when they talk about ethics because they lost the tradition of the virtues and got tangled up in failed Enlightenment projects to refound ethics on a rational, post-Aristotelian basis. I think Dreher really believes that Western Christians have lost the culture wars and are sinking towards extinction under a thousand-year flood of “barbarian” cultural nihilism. They're wrong, but they're not completely wrong. Their concerns are overblown but far from unfounded. And it's probably only because they had these exaggerated clickbait fears that they had any impact. If After Virtue had been more modest in its diagnosis, if The Benedict Option had been wiser and not balanced, they might never have been widely read.

But the clickbait-y civilizational pessimism of MacIntyre and Dreher obscures an important truth, namely, that the Benedict Option is a liberal idea.

For thousands of years, mankind was enthralled to the concept of sovereignty. Some thug would kill his way to the top, and boast a lot, until he arrived at lots of extravagant claims, such as being a god. Many would submit and flatter out of cowardice. Some would refuse or, more likely, simply not manage to do so, and be degraded or enslaved or killed. All stories except the self-serving stories of the sovereign would be suppressed. And some would go along with it from a genuine will to the common good, in the belief that coordinating on one supreme overlord was the only way to avoid a destructive struggle for power. Better one tyrant than many. Lies and slavery were the price of peace.

Then began the slow breath of liberalism. Its forerunners included the Greek democracies, the Roman Republic, and above all, the Jewish law, God-given and popularly enforced, with little room for kings and not at all for divinized kings. With the baptism of Constantine, a great historic frontier was crossed, and kings ceased forever to claim to be gods, though it took a little while for the change to reach backward places like Japan. Slowly, the idea grew up and settled in that law is rooted in the will of the people and the consent of the governed, and practical experiments to implement that began in the Middle Ages. Of course, the idolatry of the state took a long time to die. It was spectacularly exemplified in Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia, but the so-called “liberalism” of hegemonic secularist left-leaning democratic semi-socialists in the late 20th century was also stained with it. Where do rights come from? From the government. And it can make more, if it's so chooses.

Actually, they come from God, as the real intellectual fathers of liberalism, like John Locke and Thomas Jefferson, knew perfectly well. MacIntyre and Dreher miss their target. They blame liberalism where they should be blaming secularism. They have a grievance against the Enlightenment, but the Enlightenment had plenty of wholesome Christian thinkers and wholesome Christian achievements, which we should learn from, celebrate, and build on. To some extent, secularism is a natural growth of liberalism. Liberalism has many roots deep in the Middle Ages, but its maturity is modern because it depends on recognizing that faith must be free and societies must have room for people who reject it. Good liberals were Christians who made the world safe for atheism because they knew that such was the will of God. To hold a gun to a man's head and force him to pray is not the work of God but of Satan.

But as the skeptics and agnostics and atheists were politically emancipated, they sought to detach the liberalism that had emancipated them from its very clear and explicit theological foundations. One can't exactly blame them. They thought they had the truth, and they wanted to convert the world to it, and they wanted to preserve the social order while they did so. What else could they do except try to reconcile the liberal political order they believed in with the godless universe they believed in? But it doesn't work. At the end of the day, there's no good reason to be a liberal except that it's the command of God. What are rights, really, and why should people have them? Where do property rights come from, if not from the Ten Commandments? Where does freedom of conscience come from, if not from God's desire to save sinners through their freely giving Him their love, to which end they must follow their own journeys, and not be corrupted into insincere confessions of faith? Secularism couldn't be liberal in any principled way, or sustainably. Most people pray, and believe in God, and arrive much of their ethics from their religion, so if you want secularism, you have to impose it from above, often rather coercively or aggressively. Thus the Soviet Union. Thus the “liberal” jurisprudence that did so much to break American democracy by subverting the plain meaning of the Constitution by secularist sophistries, and legislating from the bench against the will of the majority. Secularism is illiberal.

There is, of course, nothing remotely secularist about the Saint Alexander Nevsky parish. The community is founded on Christ and obedient to God. But there's a fair amount of democratic self-government. We have meetings, and we vote on things. Above all, the community is beyond a shadow of a doubt immaculately consensual in a way that no liberal regime, however well-intentioned, has ever been. “We hold these truths to be self-evident,” wrote Thomas Jefferson, “that all men are created equal, and endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights… [and] that to protect these rights, governments were instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed,” etc. Yet Jefferson held slaves, over whom he ruled with no consent of the governed. And the new Republic he helped to found ruled over, or simply expelled, many loyalists to the Crown and others who certainly did not consent to its rule. There was nonetheless some truth in what Jefferson wrote, up to a point. I'm not in a hurry to blame a beneficent statesman for expounding aspirational ideals that the polity he served fell short of realizing. But we at Saint Alexander Nevsky parish do live by that ideal. We really don't claim authority over anyone, outside of our own children, who does not voluntarily embrace it by a positive act.

So it has long been. The most consensual societies in the Middle Ages were the monasteries. And the monasteries were the backbone of the Church, which was the great counterweight to the pride of kings, and by humbling them every now and then made room for the beginnings of modern liberty. The Benedict Option is not post-liberal so much as post-secularist, and because it jettisons secularism, its liberalism can be purer and more authentic. It's potentially post-liberal in the sense that if the liberal political order that we inhabit were to collapse, then we wouldn't think twice about where to turn for protection. The parish would be our stronghold and we would stand or fall with it. But we don't want that to happen. And if we did have to convert the parish into a civic entity because the political order had collapsed, that civic entity would have a fairly liberal character, consensual and not arbitrarily coercive, even though an order we'd develop would not mimic current liberalism in every respect, and would have no trace of secularism. That said, I don't think the parishioners of Saint Alexander Nevsky, or similar places, would be interested in fighting a semantic war over the term “liberal.” We're content to let the hegemonic secularists usurp the name of “liberalism,” and call what we do simply “Christianity.” But since liberalism is essentially applied Christianity in the civic sphere, our practices are more in keeping with the wholesome traditions of John Locke and Thomas Jefferson than are those of the hegemonic secularists.

Unfortunately, MacIntyre and Dreher have had a falling out, in a way that discredits them both more than they seem to realize. A well-reasoned disagreement, probing for clarity, would be fine, but the spat is lacking in nuance and mutual respect. “Old Notre Dame Man Yells at Hallucination,” wrote Dreher contemptuously after MacIntyre made a dismissive mention of The Benedict Option in a public speech. MacIntyre and Dreher don't seem to quite realize how much they need each other. Dreher’s thesis and project is more subversive and intellectually demanding than he can sustain without MacIntyre’s authority. He positions himself, in the book, as a thoroughgoing disciple of MacIntyre. He's completely laudatory and uncritical. The book tries to understand MacIntyre, to unpack and explain MacIntyre, but above all, simply to apply him as the sage of the age who needs to be followed. Dreher needs MacIntyre. If MacIntyre thinks he's gotten something wrong, Dreher of all people ought to listen. For his part, MacIntyre condemns two centuries or moral philosophy, and the intelligentsia that spearheaded and spread it, as off track and futile. Yet he doesn't want to end on a despairing note, so he concludes his famous book with the hope for a “new Saint Benedict” who will catalyze the formation of communities in which the virtues can begin to be pursued again. He needs that to be possible. It's important to the plausibility of his whole philosophy that the Benedict Option be able to work. He wants to appeal over the heads of his own intellectual class to some kind of popular wisdom, and it would have to be embodied in someone like Dreher, a pavement-pounding, interviewing journalist finding people who are trying to live the solution to the problem that MacIntyre diagnoses, spreading the word, encouraging the movement. MacIntyre ought to have been waiting eagerly for someone like Dreher to spread his ideas beyond the Ivory tower. He needed a popularizer. That doesn't mean MacIntyre can't find that Dreher gets a few things wrong. But he ought to take him seriously. The dismissive disdain is unbecoming.

I hate to see these two thinkers, both of whom I admire and to whom I am deeply indebted, quarrel like this, because I value the idea for which they are the most prominent spokesmen, and their quarrel damages that idea a lot. But I think it occurred because they both made the mistake of thinking the Benedict Option is an illiberal idea, and liberalism is so broad that anything outside it is either hopelessly, vague and abstract, which is MacIntyre's problem, or wicked and repugnant, which is Dreher's problem. Dreher, unfortunately, has fallen into an angry populist nationalism that is very inappropriate for a Benedict Option champion. MacIntyre is right to find that repugnant. Angry is entirely the wrong mood to be in. I kind of see why he has to be that way. Angry sells. As a writer who makes his living online, he's falling into angry as his way to draw the clicks. But a practitioner of the Benedict Option should be humble, grateful and hopeful. We at Saint Alexander Nevsky aren't angry. We have it good, and we wish everyone well. We can hardly claim to be populist when our way of life is a sweeping rejection of contemporary popular culture. And we're not nationalist: we welcome all comers, from many nations, including illegal immigrants, as Christ commanded.

If MacIntyre had addressed Dreher intimately, lovingly, and seriously, using the words of Christ, then maybe Dreher's respect for MacIntyre would really have woken him up and changed his heart. But the mere sneering of an over-educated philosopher at an earnest and hard-working if clumsy-minded journalist was never going to do any good. MacIntyre is to some extent to blame for Dreher's mistake. MacIntyre himself never recovered sufficiently from his youthful Marxism, and, even as he developed ideas crucial to the revival of a conservative Christian counterculture, he felt a compulsion to retain some sort of sweepingly radical rejection of the culture where capitalism flourished. He wouldn't blunder into angry populist nationalism himself because he's too civilized, too shaped by the liberal civilization that he has inhabited all his life, yet notionally rejects, on inadequate grounds. So when confronted with a wayward admirer like Dreher, MacIntyre can't talk him back from the cliff edge in the most effective way, which would be to mingle Christian themes with mainstream liberal values and urge him to be inclusive, fair, evidence-based, and think about others. He has to keep playing the role of the post-liberal philosopher, and somehow distance himself through sophistry from the ugly fruit of the spurious post-liberalism that he irresponsibly permitted to infect his thought.

The Benedict Option is no reason to throw out Western civilization's baby with its bathwater. You can strive to practice the Benedict Option and still be patriotically loyal to the Constitution and proud of America's heritage of freedom. To the extent that the Benedict Option represents a rejection of and a refuge from certain elements, tendencies and trends in American life, those trends are much more recent, shallow and special. It's gay marriage, the trans movement, and to some extent the broader Sexual Revolution, from which it's urgent to be as untainted as you can. Of course, there has always been a lot of greed and consumerism and lust and irreverence in society, and there has always been a monastic impulse to flee from it. That's valid but not at all special to our times. We shouldn't try to rewind history to the 1950s, or the Middle Ages, or any other historical.. Human societies have never conformed to the Christian ideal, or for that matter to the liberal ideal which is derived from the Christian ideal. The Benedict Option way is to forsake prescriptive grand plans for society and work at the micro level, trying to build a wholesome community from day to day. Let's try to live by the Gospel teachings as best we can amongst ourselves, and let the chips fall where they may.

I mentioned above that there are off-ramps, legitimate reasons for pious Christians not to practice the Benedict Option. I won't go into it too much since this post is so long already, but essentially, you may have good reason to think that you're doing good by being more involved with the world than that. Devout Christians who worship in hometown parishes or convenience parishes can strengthen the faith of less serious Christians who might attend, or meet sojourners and seekers and encourage or instruct them. Christians may reasonably feel they have a duty to stay in close touch with unchurched or semi-churched friends and family, and to try to be a light to them, and be alert for opportunities to lead them to Christ. And Christians can do much good in secular occupations too, sometimes. They might be scientists finding ways to combat terrible diseases, philosophers combating scientific materialist reductionism and defending richer ontologies that are more hospitable to faith, business leaders commercializing new products and creating jobs, filmmakers producing wholesome and edifying entertainment that inspires virtue, or soldiers fighting just wars. Not everyone has to be “monks.” We need “knights” as well. And of course, my heart goes out to the many, many people who yearn to be part of the Benedict Option community but simply don't have the chance.

But I'm grateful that God has let me to a place where I can thrive in the company of pious friends and strive to build up a wholesome community, and do not need to fear the invasion of wicked moral fashions. I hope that many will follow our example, or if God wills, come join us.