The Almost World Policeman

How Post-Cold War US Foreign Got Off Track. And the Future Return of the Forward Strategy of Freedom

After the Cold War, the human race almost possessed an international order comprehensively based on international law, backed up by the credible threat of overwhelming force, so that it was incentive compatible for all regimes to behave peacefully.

The threat of force came first and foremost from the US, which was poised to serve as a kind of world policeman, along with allies who tended to be eager to bandwagon with the United States, adding strength and legitimacy to its cause.

The logic of such an international order is: (a) that peace is good, but it needs rules to settle disputes that arise, and prevent them from turning into wars. But rules have little impact without enforcement. In order to make it incentive compatible to follow the rules for states that have grievances or frustrated ambitions, (b) some kind of world policeman is necessary. The US was serving a little intermittently and half-heartedly, yet still, on the whole, sufficiently, as a world policeman in this era.

Unfortunately, the phrase “world policeman” was and is usually used pejoratively, as a complaint or an accusation.

Not always, and anyway, there was an element of semantic accident in that, for other terms with similar meaning were better liked. “US world leadership” had positive connotations in the US, while “US protection” was widely valued abroad. Still, the fact that neither Americans nor the rest of the world warmed to the phrase “world policeman” as a description of a role they wanted the US to play in the world is symbolic of substantive unease with an arrangement in world affairs that was actually more or less realized for a decade or two after the end of the Cold War, and which produced a more peaceful and prosperous world than ever before in history.

I don't want to dive too much into data here, but check out this visual about the history of wars.

Source: War and Peace - Our World in Data

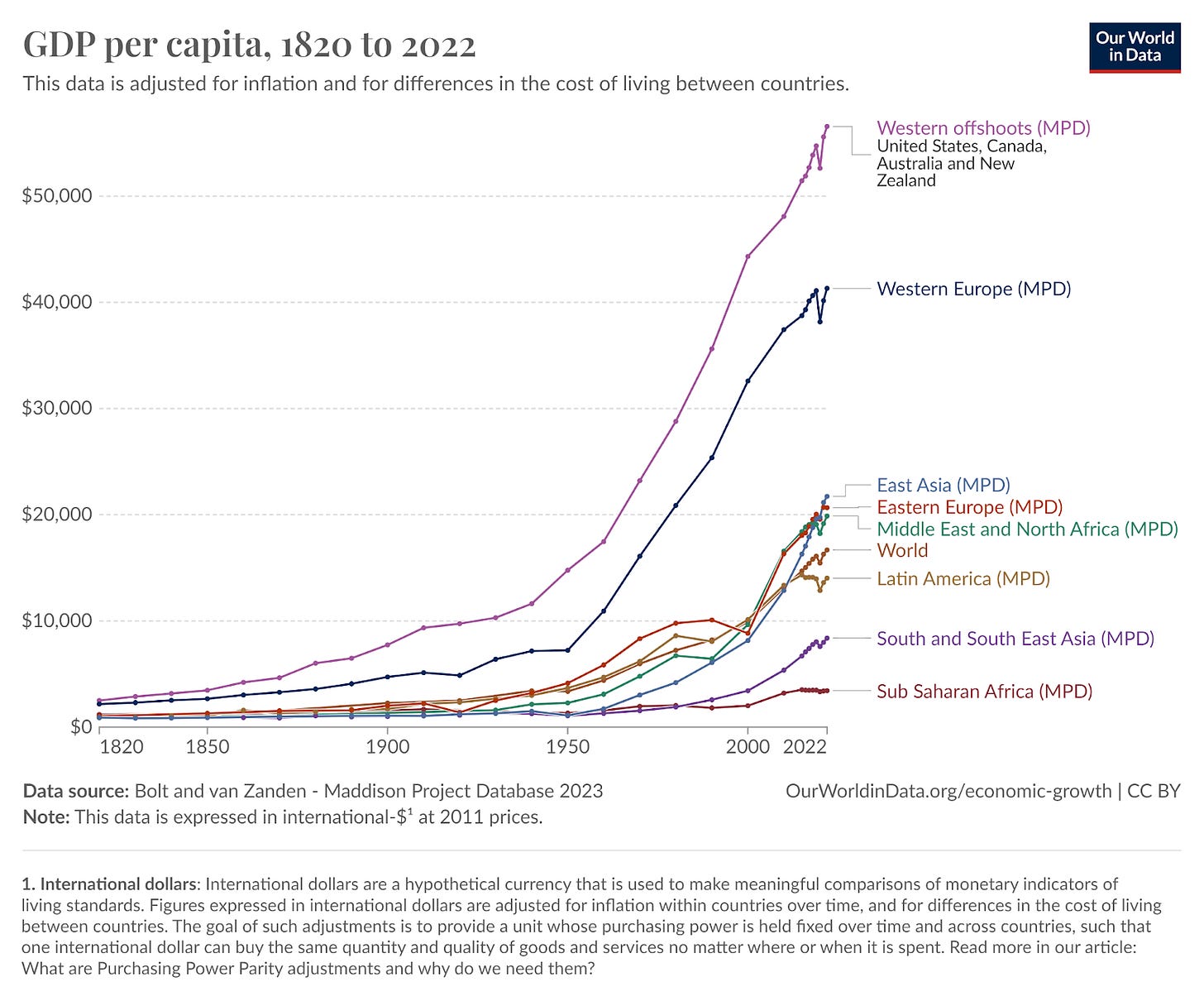

The period 1991-2011 was remarkably peaceful, in the grand scheme of things. And look what was happening to economic development! Note that the broad-based takeoff in GDP per capita coincides with roughly the year 2000, just when the post-Cold War liberal world order was consolidated.

Source: GDP per capita, 1820 to 2022 (ourworldindata.org)

It took a little while for the post-Cold War peace and the neoliberal “Washington Consensus” of relatively free markets and globalizing policies and institutions to produce the widespread economic growth and convergence that had been predicted. But by the 2000s a new global middle class was finally experiencing a sustained elevation of their living standards.

For peace and prosperity, then, the post-Cold War years look like a golden age, the best era in the history of the world. Nonetheless, there was a lot of discontent. And a lot of it looks merely ignorant in retrospect. It was very fashionable to blame the US for being so violent, warlike, and/or imperialist, even as the US totally eschewed conquest, and the era was very peaceful compared to the past and to likely futures, one of which has now arrived. It was very fashionable to blame capitalist globalization for world poverty, when in fact world poverty had long preexisted capitalist globalization, and capitalist globalization was beginning to create the most effective progress against world poverty in world history. The discontent was ignorant but understandable, since it's hard for people to piece together the big picture of what's happening, especially when a revolution in media, the emergence of the internet, greatly changed people's information set.

Some of the discontent in the great post-Cold War neoliberal moment focused on the peculiar global ascendancy of the US and its allies at this time, embodied in the tendency for them to behave as the world policeman. People who thought the world was suffering (which it was, as always, though less so than usual) tended to blame that suffering on the United States and the world order that it was leading.

In America, the concept of “world policeman” was unpopular because Americans were often reluctant to shoulder the disproportionate burdens that it implied. It implied that America must stand ready to fight all over the world, not for the “national interest” (a problematic phrase but it at least implies more choice and less duty) but to enforce international law. We did that to some extent, but we didn't exactly like it.

On the other side, many foreigners didn't trust America to be the disinterested enforcer of international law, and they heard “world policeman” as “world dictator.”

The US acted effectively as a kind of world policeman in key actions such as the liberation of Kuwait from Iraqi occupation in 1991, and even more in its explicit or perceived threats of action, e.g., against the forcible reunification of Taiwan with China. Other interventions or threats of intervention in Yugoslavia, Rwanda, East Timor, Libya, and elsewhere embodied a world policeman function for the Western powers, as well as police actions at sea in protection of international commerce, and so forth. Such actions were publicly motivated by the defense of international law and the protection of human rights, more than by Western self-interest, and in fact it was hard to see any connection between these actions and the West's geopolitical interests, except in the sense that the maintenance of a robust regime of international law was itself beneficial for the West, which wanted international peace because it was good for the West's security and commerce.

In establishing the US-led West as world policeman, the 1991 Persian Gulf War, which liberated Kuwait from Iraq, was disproportionately important. That was the first moment when the UN-led world order which the World War II allies had instituted actually worked as intended. One country invaded another, the UN stepped up with condemnations, the world's leading countries mobilized militarily against it, and the aggressor was driven back. Ideally, the same thing would happen today with Russia and Ukraine as happened in 1991 with Iraq and Kuwait.

That said, did the US fight for (a) international law, or (b) oil? In one sense, it didn't matter. In the Persian Gulf in 1991, the motives aligned. Both the US’s interest in cheap oil and the support for international law dictated a war against Saddam to drive the Iraqis out of Kuwait.

But in another sense, US motives in the 1991 Persian Gulf war were all-important. If the US was fighting to uphold international law, the precedent was predictive of future actions to punish aggressors all over the world. If it was just fighting for oil, violators of international law that did not trespass US economic interests might feel safe.

Fortunately, the war was presented as enforcement of international law. That helped. And even if Americans might not have gotten over their gun-shy post-Vietnam isolationism without oil to add national interest urgency, yet the victory turned out to be so easy that it made future war by the United States in defense of international law seem much likelier. It was a powerful deterrent. And for a decade and more, a widespread conviction settled in that aggression was no longer possible because the US was standing guard as world policeman with overwhelming military force and a peerless array of allies.

In 1991, the United Nations operated the way it had been intended to operate when it was first established in the 1940s. It had never worked as planned, because it was a system of collective security which assumed shared interests and responsibilities among peace-loving and reasonably well-aligned nations. The Cold War made the United Nations dysfunctional, since adversaries sitting on the UN Security Council vetoed the global body into impotence most of the time. But in 1991, the United Nations authorized an action against aggression, which a coalition of willing duly enforced, with a strength that hardly any country in the world could have hoped to resist. The UN then became a force multiplier for the impact of that war, translating its demonstration effect into a credible threat backing international rule of law all over the world. 1991 crowned not the US but the UN as leader of the world order, but the US was the power behind the throne.

The problem with the world order which the UN embodied after 1991 was that international law was based on national sovereignty, which logically provides impunity for dictators and genocidaires. If international law makes national borders sacrosanct, it logically follows that national governments, no matter how weak, can treat their subjects as badly as they like. In upholding international law, the world policeman could hardly help protecting dictators, too, even genocidal dictators.

This was made painfully clear in the crises of the 1990s, such as Rwanda and episodes of ethnic cleansing in the disintegration of Yugoslavia. The West’s overwhelming power gave it a kind of responsibility when atrocities occurred, not in any way at its behest or in its interests, but thanks to its inaction, since it could have stopped them.

Principles of national sovereignty also forbade secession, but this went against much of the content of both liberalism and anti-colonialism. The United States itself was founded through an act of secession, and its Declaration of Independence asserts what amounts to a right of secession in circumstances which pretty frequently occur. In 1945, much of the world was ruled by European colonial empires, and all sorts of nationalist aspirations to independence from these empires could easily be asserted as applications of the principles in the American Declaration of Independence. With both of the world’s superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union, being ideologically anti-colonialist, European nations trying to hold onto their colonial empires found themselves rather friendless, and colonialism slowly collapsed, often with disastrous results. In spite of this, the UN-led world order didn't really endorse secession in principle, and the aspirations to independence of colonial subject nations was sort of grandfathered in as an exception. By the 1980s, colonialism had essentially vanished from the world, and the new national borders established in the process were invested with the sanctity that a world order based on international law and collective security had to give them. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the borders of newly independent post-Soviet republics were also invested with the same sanctity, though they had appeared but yesterday and largely lacked any deep historical roots or deep foothold in the popular imagination.

The Chechen war that began in 1996, in which the Russian Muslim-majority province of Chechnya tried to secede but was brutally subjugated, exemplified the West’s adherence to its principles of national sovereignty, even when it arguably ran against the West's interest in weakening Russia, its greatest historical enemy, and even though Russia's suppression of Chechen aspirations had appalling humanitarian consequences. Russian borders, too, were sacrosanct.

In response to the Rwanda and Yugoslav crises, humanitarian-oriented thinkers framed an idea of a “responsibility to protect,” that is, of the international community to protect victimized minorities, especially against genocide. The new doctrine suggested that secession, too, might be supportable, at least where it seemed like the only way to fulfill the responsibility to protect by creating a viable non-genocidal regime for victimized regions. The international community resisted embracing this conclusion because it would be excessively disruptive to the new global order. But it still made inroads, because the moral case for it was so strong.

The disintegration of Yugoslavia was not exactly an exception to this rejection of secession, because Milosevic's regime in Serbia had no interest in ruling a united Yugoslav territory. It only cared about ethnic Serbs and was happy to allow the departure of territory and people which were clearly non-Serbian. Nonetheless, Yugoslavia did set a precedent which could favor secession abetted by the West.

The new doctrine of humanitarian intervention expressed itself in the Kosovo war of 1998, which was distinct from the earlier Yugoslav collapse because Kosovo was an integral part of what Serbs thought was their country. Serbia wanted to do to Kosovo what Russia had been doing to Chechnya since 1996: crush an independence movement in defense of national sovereignty. But this time it was too close to the West. As in 1991, the West fought in a way that kept the war virtually bloodless for itself, with with nasty trade-offs on the ground, where NATO troops might have prevented interethnic violence in a way that NATO planes could not. The West was not fighting for independence for Kosovo, but only to prevent the kind of genocide that Serbia had already perpetrated elsewhere. But the cowardly manner of the West's intervention, with strict reliance on the kind of air power that had proven so devastating in 1991, but only for destruction and not for delicate manipulation of the situation on the ground, deprived it of the power to dictate the terms of a peace settlement. The West became a hostage to local proxies with which it had aligned itself, namely, the Kosovo Liberation Army, which didn't want reintegration with Serbia on terms of respect for human rights, but simply independence.

Consequently, the Kosovo intervention fundamentally marked a break of the West from the principle of national sovereignty, without putting any clear new principle in its place. For ten years, however, an explicit break was avoided by non-recognition of Kosovo's de facto independence. The fiction of Serbia's ongoing sovereignty in Kosovo provided the West with a kind of not-very-plausible yet still legally tenable deniability about having abrogated national sovereignty principles.

Russia took a particular interest in Serbia, partly for ethnic reasons, since Serbs are historically Eastern Orthodox Slavs and thus closely resemble Russians. Also, Russians have regions with Muslim minorities that have long comprised part of their national territory. The precedent of Kosovo's secession threatened to encourage secessionism among Muslim ethnic groups ruled by Russia.

When in 2008, the West finally surrendered to a fait accompli by explicitly recognizing the independence of Kosovo, Russia very soon took advantage of the new precedent to project power by launching an invasion of Georgia, after preparing the way by instigating traditionally Russian-backed separatists in South Ossetia to start shooting at Georgian troops. Russia has been addicted to imperialism for centuries, as the result of it is the chief national enemy of all its neighbors to the west.

In failing to fight to defend Georgia's sovereignty against Russian aggression, the US and the West went far towards abdicating the role of world policeman. Nonetheless, the manner of Russia's intervention in Georgia, emphasizing continuity with liberal principles of responsibility to protect, and only supporting secession, not annexation, still displayed a certain deference to the UN-led world order.

In 2014, Russia proceeded to occupy and annex the Ukrainian province of Crimea. This represented a new kind of breach with the post-Cold War international order, by reintroducing imperial expansion, which the international order had sought to abolish. However, the bloodlessness of the annexation of Crimea, though hardly reassuring as it evoked the early bloodless conquests of Hitler, did obscure its aggressive character, and mildly mitigated the damage to the integrity of international law, since there were not many places in the world where annexation of foreign territory could occur bloodlessly.

But Russia immediately doubled down by supporting secession by some eastern Ukrainian provinces, which were obviously candidates for Russian annexation. And here, the move was not bloodless. Nonetheless, Russia maintained a certain distance from the separatists, so it was not quite a pure case of imperialist aggression. Still, the integrity of international law is clearly being eroded step by step

Finally, in 2022, Russia's explicit invasion of Ukraine for purposes of conquest decisively ended the post-Cold War era of peace based on international law, at least in Europe. The liberal peace of the post-Cold War years has given way to another age when hostile blocs confront each other and force matters more than law.

There's a sense of inevitability about this sequence. A bluff was called, step by step, and it was inevitable, in a messy world full of conflicting passions and aspirations, that it would be called.

And yet there's plenty that the West could have done to stop the tragedy. The West could have committed itself to, and resolutely followed through on, being the world policeman. That means, first, that it would have needed to assert a comprehensive threat of force against violations of international law, and then acted strongly whenever such violations took place. Also, it would need to have strengthened the legitimacy of international law by fostering a rich deliberative process.

Concretely, the West should have put boots on the ground in Kosovo in 1998, both to mitigate the immediate humanitarian crisis more effectively, and to maintain control over the breakaway region so that it wouldn't be cornered into accepting a fait accompli later. By leaving it to Kosovars to defend themselves, providing only air cover, which, though dramatically powerful in a way, was very poorly fit to purpose, the West ensured that power would be assumed by local forces with no interest in maintaining the territorial integrity of Serbia for the sake of integrity of a larger system of international law. The West was simply too cowardly in 1998 to risk the lives of its soldiers, so it botched the crisis, in a way that did more than anything else to set in motion the slow collapse of the whole world order.

Even more importantly, the West should have confronted Russia much sooner and much more strongly. The West's own anti-secession principles were rightly applied to Chechnya in 1996, yet the West could have put a conditional threat of intervention on the table, and in return for its non-support of Chechen Independence, insisted on Russian respect for Chechen human rights. In 2008, it was inconsistent with and fatal to the whole scheme of world peace based on international law for the West not to signal a strong readiness to put in troops, and fight Russia if need be, in defense of the territorial integrity of Georgia, a country that was in effect being partitioned by imperialist aggression, albeit still under a rather threadbare cloak of humanitarian intervention. Probably all-out war with Russia to restore Georgian control of Abkhazia and South Ossetia would not have been the right move at that time, but there should have been threats and brinksmanship, and escalated defense spending, and firm promises of never again, etc. The West's failure in Georgia was particularly damaging because Georgia was a close US ally, which had actually been fighting alongside us in Iraq. And after 2014, the prospect of NATO troops fighting to restore the territorial integrity of Ukraine should have seemed like a matter, not as if but of when.

Now it's too late.

I would still like to see NATO threaten Russia with sending troops to fight against them in Ukraine. But it would no longer be in defense of a peaceful world order based on international law. It's too late for that. That order is gone. The post-Cold War world ended when Russia launched a full invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, with the apparent blessing of China. Now almost a third of the human race inhabits countries whose regimes are more or less explicitly at enmity with a law-based world order. We need to look back further in history for guides to how to conduct ourselves now.

The best analogy is to see this as Cold War II, resembling and differing from Cold War I much as World War II both resembled and differed from World War I. Again, China and Russia are defiant, in the grip of hostile ideologies. But again, their mutual trust and alignment of interest is very imperfect, which can be exploited. Again, the West is richer, freer, and more technologically advanced, and also should enjoy the moral high ground, because its model of society is far more just and conducive to human flourishing. Its moral advantage is jeopardized for a good reason and a bad one. The good reason is that Western free speech ensures that critics will thrive white Western society itself, and supply much information and ideation to enemy propagandists. The bad reason is that the West has long been much more stingy, exclusive, and probably still tacitly racist than it ought to be. Foreigners’ envy and admiration of the West is sometimes a reason to hate it, because we won't share.

But I think another historical analogy is applicable as well. When Britain defied Germany in 1939 and 1940, it had the courage but not the strength. The British were outnumbered, as often before, but they could no longer depend on the superior per capita effectiveness of their society. They needed their enemies to fall out, as Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union duly did. But they also needed the United States. And the manner in which the United States came to Britain's rescue also forever dethroned Britain from the role of leader of the Free World which they had often played. This was not just a matter of prestige. Britain's practical interest in the maintenance of its empire was fatally jeopardized by the new ascendancy of the United States, which never attacked Britain's empire, but also had no belief in it or willingness to help Britain maintain it.

Like Britain in 1940, the US today, even with its Western allies, lacks the manpower to match itself against China. And it can no longer take for granted a superior per capita effectiveness. Like Britain in 1940, the US has great potential allies in the great democracies of the global South, such as India, Indonesia, Brazil and South Africa. They are certainly much more naturally friendly to the United States and the West than to the axis of China, Russia and Iran. Yet they are far from fully satisfied with Western leadership of the world order. They have many just critiques, as well as legitimately differing preferences. The West can't expect them to simply stand up and fight for the Western-led world order of the immediate post-Cold War years. It should find a way to ask them to share both the burdens and the privileges of leadership.

Whatever the rules of a future world order turn out to be, they'll need an enforcer. If there is to be international law, there needs to be a world policeman. So if history calls on the West again to serve as a world policeman in defense of a benign world order, we should step up and do the job bravely, vigorously, and well. We should be willing to accept disproportionate burdens for the benefit of world peace, in a spirit of noblesse oblige, as the part of the world that has longest been ennobled and enlightened by the blessing of liberty. A policeman is not a judge, and being world policeman doesn't mean you get to dictate international law. We should stand ready to enforce the judgments of a duly constituted, generally beneficent, participatory world order, even if we sometimes don't agree with them, or find them to be contrary to the immediate national interest.

Nonetheless, a policeman can have scruples, and often the character of law is shaped by the scruples of policemen. And we can be a little choosy about what kind of world order will merit our service. And this brings me back to one of the episodes in recent foreign policy history that I skipped over.

I wasn't trying to be comprehensive, in any case. I was trying to elucidate the evolution of the world order, so I focused on moments that set important precedence and affected the direction of that evolution. The US war in Afghanistan, though it lasted 20 years, doesn't seem very important for the evolution of international law, since it was generally and straightforwardly accepted as a legitimate war of self-defense by the United States after the terrorist attacks of 9/11. Similarly, the US intervention in Libya in 2011, with vaguely humanitarian motives amidst a geostrategic muddle, illustrates but didn't really alter the pre-existing muddle of national sovereignty and human rights principles that had been shaping Western foreign policy since the 1990s.

But the liberation of Iraq in 2003 was important.

It was important, first of all, in winning the Global War on Terror, and in the very strange and roundabout way, which was the last thing that Al Qaeda must have expected when they attacked the Twin Towers in New York. The obvious thing for the West to do in response to 9/11 was to fight Islamic terrorism in alliance with the many dictators who dominated the Muslim world, who tended to hate the terrorists for their own reasons, and in any case, found it very advantageous to be allied with the United States. That would only deepen the long-standing hypocrisy of the West, which preached democracy and human rights and yet had long allied itself. With all sorts of vicious dictators in the developing world. It would therefore played into Al Qaeda's hands in an important way, but we might have been able to win the war on terror on those terms, with much loss of the moral high ground.

George W. Bush refused to do that.

Instead, by liberating Iraq and seeking to stand up a liberal, rights respecting democracy in the heart of the Arab Middle East, the neocon West hurled down the gauntlet to Al Qaeda in a way that they had to answer. They couldn't really compete with the appeal of Western democracy as a societal model. But the whole world order in the 1990s tended to make that societal model seem unattainable for the underprivileged majority of mankind. Vast regions of the world, especially those under the sway of Islam, had hardly any liberal democracy, and no prospect of getting it, and the West, which piously paid lip service to an ideal of liberal democracy for all, in practice conspired with the oppressors. It was a kind of global apartheid, democracy for me and not for thee, and against that, Al qaeda's message of islamist Revolution might succeed. But if liberal democracy for the Arab Middle East was really on offer, Al qaeda's message was doomed to lose its appeal by comparison. And so Al Qaeda had to fight, and they did, but in the process, ugly terrorist killings of Arabs poisoned their reputation and ruined their prospects of earning recognition as the spokesmen for the oppressed Muslims of the Middle East. So when bin Laden was finally killed in 2011, it was hardly even an event. He didn't become a martyr. He didn't matter anymore. His cause had burnt itself out in the battlefields of Iraq.

Not that George W. Bush was planned all that. There is a kind of luck that is a side-effect of idealism. Generous deeds tend to pay off in unexpected ways. In any case, it's of limited relevance to the present study.

The thing to stress here is that while Operation Iraqi Freedom was successful in certain ways, starting with the simple fact, which is so politically incorrect to state nowadays, that we won the war by overthrowing Saddam, it was also a failed attempt to alter the trajectory of the world order. In this connection, the contrast between the presidencies and foreign policies of Bush Sr. and Bush Jr. is very instructive.

When Bush Sr. led the United States to war in 1991, it's doubtful whether most Americans cared very much about Kuwaiti independence or the larger principles of international law that were at stake. There was some fear-mongering about what Saddam's Iraq was capable of, and there was the price of oil. But Bush Sr. added a lot of inspiring language and thereby changed the meaning of the war, and the nature of the precedent that it set. In doing so, he articulated principles that defined the world order in the immediate post-Cold War years, with impacts that were very beneficent in some ways, and very sinister in other ways. For the US also set a fateful precedent by stopping, by contenting itself with the liberation of Kuwait from Iraq, and left Saddam in power to commit more atrocities. The precedence seemed to show that aggression would be stopped and punished, but that the sovereignty of even the most odious dictators within sacrosanct frontiers would be respected. Within that framework, all human rights violations were, in a sense, authorized.

And so, in a crucial way, Bush Jr was paying down his family's debts to history, and undoing it wrong that his father had done. Like his father, he superimposed a lot of idealistic language and lofty principles on a war that the American people supported for less generous reasons. What the large majority of Americans who supported the war in 2003 thought the reason for the war was is hard to say. No doubt, the median voice in public opinion thought the connection to 9/11 was closer than it really was. But George W. Bush made it the centerpiece of his “forward strategy of freedom,” and tried to make it stand as the authoritative precedent for a world order that would no longer tolerate tyranny, as his father had made the Gulf War of 1991 stand as the authoritative precedent for a world order that would no longer tolerate aggression.

I'll go out on a limb and say that it was the highest ideal that the leader of a great power has ever advocated. As far as I know, at least. But the effective realization of the vision that Bush articulated in his Second Inaugural of 2004 would have required, to say the least, a much greater willingness on the part of Westerners to take risks and make sacrifices for generous dreams then they turned out to have.

The unraveling of the post-Cold War world order had nothing to do with the subversive precedent of 2003. It was already baked in, and unfolded quite irrelevantly to Bush's Global War on Terror. If anything, the US-led liberation of Iraq strengthened the world order by displaying the West's willingness to fight, and not just with air power, but effectively, on the ground, in ways that got its soldiers killed. At the same time, a comprehensive repudiation of neoconservatism and idealism was managed by elites, helped by the moral laziness of public opinion, so as to mitigate as far as possible the dangerous and demanding precedent that the liberation of Iraq had set.

But as friends of liberty around the world mobilize to resist a new crop of tyrants and aggressors, and as we try to define the ideal for which we should strive, we can do no better than to set our sights again on the forward strategy of freedom, and a world without tyranny.

As usual, the standard to live by is the Golden Rule. Do unto others as you would have them do unto you. And what would you have the prosperous and free West do for you, if you were the unfortunate victim of a brutal tyranny? That's right. Liberate you. Not always by war since it's so messy and dangerous. Maybe by accepting you as an immigrant. Maybe by threatening a liberation and thereby scaring your rulers into better behavior. But yes, in some extreme cases, by military overthrow of the world's most despicable regimes.

I hope that will emerge as the ideal for which Cold War II will be waged. If so, George W. Bush will resemble Woodrow Wilson in being a leader whose foreign policy idealism was ahead of his time.