Sometimes there's a hot topic of debate, and I find myself frustrated with how it's framed, because I disagree with something both sides seem to take for granted, if only because they're trying to win an argument. Inflation is a case in point. Republicans tend to blame Biden, while Democrats tend to blame Covid-driven bottlenecks, but everyone takes for granted that inflation is bad. Meanwhile, the economy of 2021-2022, when inflation peaked, was not only good but positively redemptive, the best in a generation for many who badly needed the help. And it could have gone on, but the Fed is working against it. It has to do so because of its ill-chosen, fighting-the-last-war mission, and no one resists and demands the right kind of course correction, because everyone is stuck on the idea that inflation is bad.

I want to reset people's thinking. The real lesson of 2021-2022 isn't about who's to blame for inflation, but about how the beneficent post-pandemic boom showed in practice what theoretically-savvy economists should have known, and some did recognize to some extent, for over a decade: that the US economy long needed some moderately elevated inflation to shift it into a high growth gear and lift up people long left behind. But the inflation blame game got in the way of people recognizing that, and now the interest rate squeeze risks dragging us needlessly back into the Great Stagnation. That's not a prediction of recession. It's a prediction that we'll keep underperforming our potential because of maladroit monetary policy, which was temporarily fixed by extremely expansionary fiscal policy.

Again: everyone seems to agree that inflation is bad. With one interesting exception: economists, who understand the matter best, generally don't think that inflation is merely bad, plain and simple, full stop. The mainstream economist view is actually that a little bit of inflation is good, and that's why the Fed doesn't target 0% inflation, but 2% inflation. We'll see why they think so, and why they probably shouldn't draw the line at 2%. But 2% is about as much inflation as economists can get away with wanting. People don't notice 2% too much, and you can call it "stable prices." But beyond that, the unpopularity of inflation is too much for the experts to want to go against it.

People hate inflation because it's confusing and they think it makes them poorer. When prices are higher, your money buys less. Yes, but you probably make more money, too. The truth is that if higher prices are making everybody poorer, that isn't inflation. Inflation's going on, but a real decline in economic activity is what makes people poorer. That's not a substantive point about economics, it's just math and definitions. If (a) prices rise and (b) everybody's purchasing power falls, that's two phenomena, not one, and the name for (b) is negative economic growth, not inflation. There may be a causal connection, but if so, it's not from inflation to less economic activity, but from a negative shock to aggregate supply to both inflation and reduced economic activity. If, in the face of a negative aggregate supply shock, tight money prevented the inflation, the decline in economic activity would be worse. And if inflation occurs because of loose money, without a negative shock to aggregate supply, then there will be more economic activity.

That we all get poorer because prices went up isn't a thing. It can't really happen. Some people can get poorer because prices go up and their income or assets are sticky in nominal dollar terms for some reason. In the short run, that can be a lot of people, because wages tend to be sticky and most of us have money in the bank in zero-interest checking accounts. But the thing to keep in mind is that every time you pay more, someone's nominal income went up. Often, the problem is that people don't make the connection between rising prices and their own higher nominal incomes. If anything, they'll tend to take credit for their own rising incomes, while blaming inflation for higher prices. "I just earned a 10% raise, GO ME! But because of this stupid inflation, I can hardly buy more than I could before." Why do you think you got the 10% raise? Because inflation gave the boss more money, and the other bosses more money, and he had to raise your wages to stay competitive. It's all part of a system of prices roughly described by the economist's idea of general equilibrium, which makes all prices move together, more or less. But people don't understand that, and as far as I can tell, they hate inflation mostly because of a sheer fallacy.

Economists dislike inflation, too, for the most part, and they are immune to the fallacy of mere money illusion. They have reasons to dislike inflation that still make sense when you understand that inflation raises incomes as well as prices. For example, "shoeleather costs," to give it the name I heard in school, which had an old fashioned feel even then, since drive-thru ATMs were a well-established institution. Shoeleather costs are supposed to be the extra wear and tear on your shoes from constantly walking to the bank to get more cash, which you do more of in inflationary times since you don't want to hold a lot of cash, since cash keeps losing value. Obviously, that's very obsolete at a time when most payments are electronic. Maybe there's some modern equivalent, but it's not clear what it would be. Or again, "menu costs," the cost of reprinting menus all the time because inflation forces restaurants to keep changing their prices. That's still a thing, but surely it's pretty trivial. Menu costs could be expanded to the cost of constantly updating your online advertising, but it's clearly much too small to be a major drag on the economy.

The point is that while economists do have some good reasons to dislike inflation, the real downsides of inflation that aren't mere money illusion don't seem sufficient to justify inflation's unpopularity. I think what's happening here is that ordinary people hate inflation because they think it makes everyone poorer, and economists, who know that it doesn't make everyone poorer, come up with rationalizations for inflation's unpopularity, and then proceed, in their expert capacity, to develop, advocate, and implement policies that will pander to popular prejudice against inflation, even if they are damaging in other ways, and may really be contrary to the public interest. And the great economy of 2021-2022, with surging wealth and jobs galore, was a glimpse of what we could enjoy if we learned to love moderately elevated inflation.

But it's hard to explain this in the abstract. Let's turn to the data.

How the Pandemic May Have Ended the Great Stagnation like World War II ended the Great Depression

In looking at the macroeconomic data from the past few years, my general theme will be that the pandemic, and especially the public policy response to it, may have got us out of the Great Stagnation in much the same way that World War II, long ago, got us out of the Great Depression. The "may have" is there mostly as a placeholder for uncertainty about the future, because we may yet spoil it. Of course, it's counterintuitive that giant bad things like wars and pandemics can help the economy. But perhaps it will be more understandable if I explain that in the 1930s and the 2010s, the policy was in thrall to a false idea, and the urgent needs of emergency response made us do practical things that got that false idea out of the way. In each case, the false idea had to do with fiscal responsibility and especially the management of the money supply.

Anyway, let's start with the inflation time series since the 1950s in Figure 1. By the way, many thanks to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis for packaging up so much macroeconomic data so conveniently.

Figure 1

The most striking thing in Figure 1 is the great inflation of the 1970s. We had the time of stable prices in the 1960s, and then again from the 1980s through the 2010s, with a huge inflationary phase in between. That inflation left nominal prices permanently higher, which doesn't really matter but can make people long for the good old days. The 1970s had a lot of problems that weren't really related to inflation, such as oil price spikes driven by developments in the Middle East, and the exhaustion of the easy economic upgrades from the great innovations of the second industrial revolution, electrification and automobiles and planes and telephones and all that. By the 1970s, the economy was fully modernized, and could no longer grow much by the mere implementation of long available technologies. There's much more to be said about that, but the takeaway is that a lot of people learned the wrong lesson from history, and thought inflation was the cause of the 1970s malaise, when really it was more a symptom of it. That said, the high end of volatile inflation of the 1970s was avoidable and harmful. But the 1980s, too, which are remembered as a time of "morning in America" economic renaissance, had higher inflation than what prevailed in the 1990s through the 2010s, and then what the Fed targets. The 1980s can serve as a proof of concept that moderately elevated inflation is compatible with booming prosperity.

When you put the inflation of 2021 and 2022 in this longer historical context, it doesn't look so serious. The inflation rates never swelled to their 1970s heights. At their worst, they look more like the 1980s. Now they're coming down, so the macroeconomy of 2021-2022 looks like an anomalous moment, and this "soft landing," meaning disinfection without recession, is being widely celebrated. But the hot inflationary economy of 2021-2022 didn't have to be an anomalous moment. It could have become a new normal. Or at any rate, that economy was identified as a problem and deliberately combated by the Fed through aggressive interest rate hikes. So what was that immediate post-pandemic economy like? Let's see some more data. Here's unemployment:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/UNRATE

Figure 2

Wow! The plunge in unemployment shown in Figure 2, after its terrifying pandemic surge, is a wonderful relief. It stands in very stark contrast to the slow jobs recoveries after the previous three recessions. Of course, the policy response doesn't deserve all the credit. Jobs disrupted by a pandemic are much easier to restore than jobs lost in a financial crisis. We didn't quite know that in 2020, and there was cause to worry, but it makes sense. A financial crisis like that in 2008 forces people to rethink all sorts of arrangements, and that takes time. In 2020, they were lots of healthy enterprises full of mutually beneficial, sustainable employment arrangements that got disrupted by lockdowns, but that could go back to normal as the lockdowns faded.

But the policy response deserves a lot of credit too. It was far from foreordained that employment would spring back so quickly. There could well have been a major demand-side recession, which would have left employers too cash-strapped to rehire as many as they had laid off. That didn't happen because Congress flooded the economy with money. For free marketeers, this may be an unwelcome claim. They don't like the economy to be so dependent on government action like that. But it was a fairly bipartisan triumph. The CARES Act of 2020, the biggest driver of the strong recovery, got overwhelming support from both parties, and while the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, which also helped a lot, ended up passing on a partisan basis, its large cash giveaways had been fervently advocated by the outgoing president of the other party. In general, fiscal stimulus has been a bipartisan practice for decades, the difference being that Democrats prefer to do it by spending more, Republicans by taxing less. Either way, deficits go up, and there's more money in people's pockets to fuel demand. And when the pandemic hit, politicians kept it up, only much more so.

Related to the plunge in unemployment is the surge in job openings:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/JTSJOL

Figure 3

While low unemployment and abundant job openings are clearly related, the takeaway from this chart seems different. Unemployment looks like the economy getting back to normal with unusual speed. But job openings don't look a mere return to normal. There were far more than ever before, almost double as many. And it hasn't come down all that much. This is a new economy, and it seems very good for workers. But why are job openings so elevated? To that I'll return.

Closely related to the wealth of job openings since 2020 is the elevated quit rate:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/JTSQUR

Figure 4

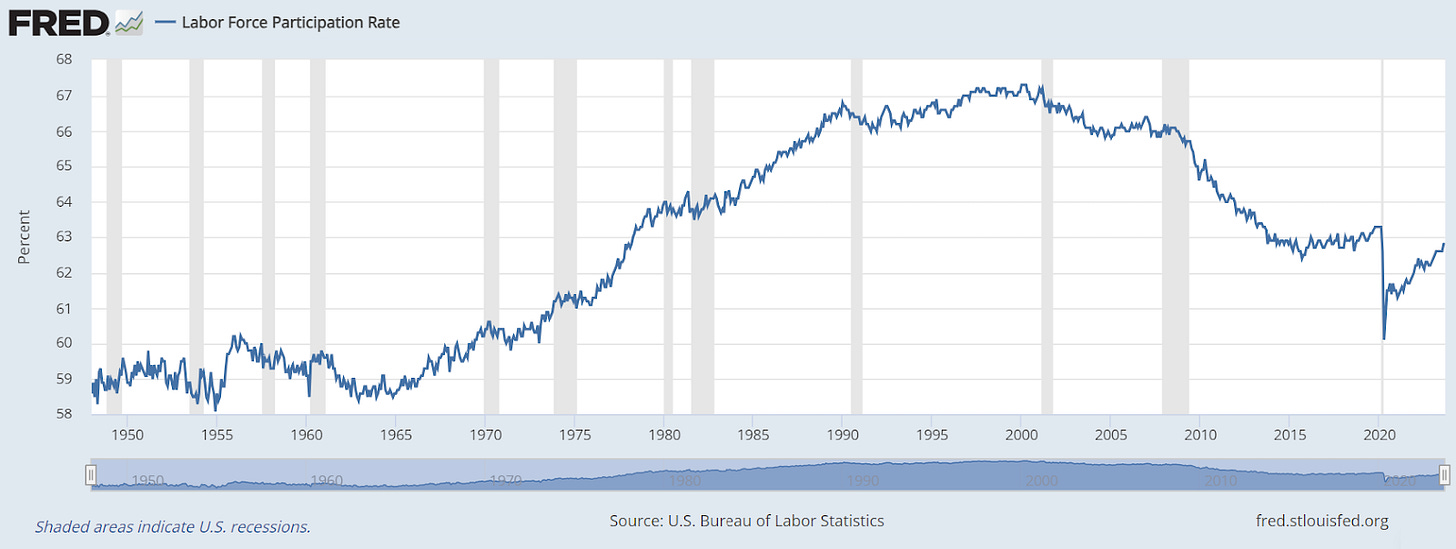

The jump in quits shown in Figure 4 sometimes got called "the Great Resignation," and there were a lot of factors playing into it. Partly, I think it was a result of the telework transition, which provided a new impetus to sorting workers and jobs. Workers with a preference for telework sometimes quit mandatory office attendance employers; sometimes it probably went the other way, too. But a lot of it was simply that a very strong labor market was a good opportunity for employees who didn't love their jobs to move on. What was not happening, though widely feared, was a lot of people giving up on work altogether. The labor force participation rate is pretty much back to normal:

Figure 5

Now, what about wages? This is the heart of the matter, the vital core of the macroeconomic social contract of capitalism. Economic security under capitalism comes from there being plenty of jobs and jobs paying enough to live on. How are we doing on that front? Let's take a look:

Figure 6

Yay! Real wages are up!

There's a lot to be said about the real wage tone series in Figure 6, and also, much that's it interest that it unfortunately doesn't show. It doesn't show anything about the distribution of wages, which matters a lot. The median worker could be doing fine while the 10th percentile is in bad shape. And I couldn't find any up-to-date time series charts that show how lower percentile workers are doing.

On the other hand, maybe median real wages are the best indicator of the health of the macroeconomic social contract after all. Some wages, probably concentrated at the lower end of the distribution, are earned by people who don't depend on their earnings to live, because they're secondary earners in a household. If teenagers with summer jobs, or wives working part-time while breadwinning husbands pay most of the bills, don't earn enough, by themselves, to feed, clothe, and house a family, that's not necessarily a problem. Median wages may shed the most light on whether capitalism is providing an adequate living standard to most people.

With that in mind, it's quite troubling that median real wages were fairly flat more often than not over the past few decades, and trended down for a while after 2008. It looked like a lot of people would end up worse off than their parents were. Doubtless, quite a few did. But since 2015, median real wages have been moving up. One thing that makes this statistic tricky to interpret is that there was a spike in medium real wages at the height of the pandemic in 2020, which shouldn't be interpreted as an actual surge in anyone's wages. Rather, it's a composition effect. Layoffs were disproportionately among manual workers and service workers, not among laptop-wielding professionals, who have higher wages on average. So you have to read the chart while ignoring the striking local peak. But we are back to full employment now, so the 2022 or 2023 data can be compared with 2015 to 2019, and what it shows is that real wages have essentially kept on their earlier upward trend. Fifteen years of stagnation have been solidly left behind. That's a huge achievement.

Another nice aspect of the post-pandemic economy is that when people do separate from their jobs, it's usually a choice:

Figure 7

In general, layoffs are bad, quits are good. Layoffs show that someone lost the job they wanted to keep. Quits mean they're moving on to something better. Obviously, there are some nuances there, but it's good if quits exceed layoffs by a wide margin, and by that measure, Figure 7 shows that the economy has never looked better than recently. But the best was 2021-2022; lately things are getting a little worse.

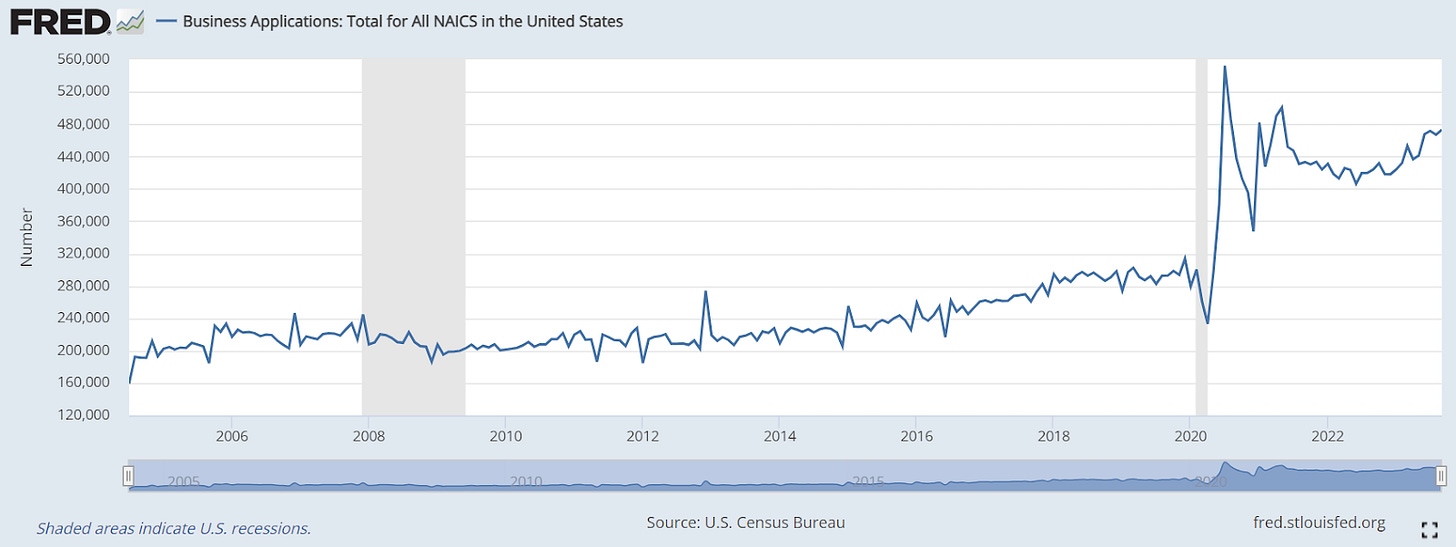

Before we move on from labor markets, there's one other startling development since the pandemic that I want to note. Entrepreneurship has jumped:

Figure 8

It's great that so many businesses are being started since the pandemic, but the change down towards the end of Figure 8 is a bit mysterious to be. I'm not quite sure why business starts have stayed elevated. Hot labor markets don't seem to explain it. If anything, they go the other way. A hot labor market is a seller's market for workers, and a tough time to be an employer. Entrepreneurship means not being a worker and maybe becoming an employer. It seems like a bad time to do that. It does make sense that people laid off during the 2020 lockdowns would try to see what they could do on the side and turn into entrepreneurs. But why keep at it when the jobs came back?

I have plenty of ideas, but they're rather speculative. Maybe the run-up in housing and stock prices put a lot more people in a financial position where they could afford to become entrepreneurs. Maybe the closure of some businesses in the early pandemic left openings for others as the economy opened back up. Maybe the complex transition to telework left a lot of people faced with stupid back-to-office mandates and they were ashamed to work for employers too stupid to run a Zoom meeting, or unable to distinguish between managing and babysitting. Or maybe people took advantage of telework to move to cheaper, more congenial places, and then preferred self-employment to returning to cramped, overpriced cities when back-to-office mandates made their new lifestyle choices incompatible with their old jobs. Maybe people tried self-employment during lockdowns, and found that they liked it and succeeded at it better than they would have expected. Low interest rates could also be a factor, encouraging the borrowing that's often needed to start a business, but like high unemployment, that reason would point to a dropoff since interest rates surged, which hasn't occurred, or not yet. Or again, maybe people saw the hot labor market and felt confident they could get a job if they wanted one, so they were more comfortable taking a risk. And maybe the sudden shift to government checks coming to everyone during the pandemic felt like a safety net people could fall back on if entrepreneurship didn't pan out.

Whatever the causes, this rise in entrepreneurship seems very promising. Entrepreneurs create jobs, add variety to local economies, and pioneer new ideas. But much will depend on whether all the new business are flash-in-the-pan affairs, or if some endure and grow.

The great labor markets are partly offset by the runup in housing prices.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CSUSHPINSA Figure 9

What Figure 9 shows is far from being all bad. For incumbent homeowners, it's good, on balance, in a complicated way. They have more wealth, on paper, and they can leverage it to borrow. They have the option of cashing out and buying a cheaper house, or renting. But some who really don't want to move and don't need to borrow might be hurt by increased property taxes. Aspiring homeowners, meanwhile, are finding homebuying a lot less affordable, even after higher wages are taken into account. But at least they can rent. Note that it is not the case that all the real wage gains are taken away by soaring home prices. Real wage gains are calculated after inflation is deducted, and inflation includes rental cost equivalent. So real wages are still rising after rising rents are accounted for. Homeownership, though, which most people order at a certain stage in life, has gotten a lot harder to achieve.

One reason why home prices are so high is that there was a building slump for the past 15 years or so:

New Privately-Owned Housing Units Started: Total Units (HOUST) | FRED | St. Louis Fed (stlouisfed.org) Homebuilding has been in a depression since 2006; no wonder there’s a housing shortage now; and it shows that real interest rates have been too high.

Figure 10

Maybe that homebuilding slump was partly justified by a graying population and a shift towards life in bigger cities. Maybe the surge in demand right after 2020 is a function of telework and couldn't have been foreseen.

But from today's perspective, at any rate, the homebuilding slump seems very inefficient. More homebuilding since 2008 would mean there would be a larger housing stock today, and prices wouldn't need to have been run up so much. It might also have helped with the problem of stagnant real wages. There would have been a lot more construction jobs all that time.

And the really sad thing is that now homebuilding is going the wrong way. It peaked just after the pandemic. Why the drop? Of course, because of the fierce interest rate hike. But lots of people still need better housing. Now housing prices are still high, and interest rates are also high, and fewer houses are being built. Too bad! We were on the right track in 2021, building more houses, but now something's gone wrong.

I've heard that has been a sharp drop in home sales, but the Federal Reserve data series on it is too new to give as much context as I would like:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/EXHOSLUSM495S (unfortunately the time series is too short but the drop in home sales seems inefficient)

Figure 10

Still, for what it's worth, home sales seem to have dropped dramatically over the past year. Now, so much volatility in homebuying seems pretty inefficient. Home sales ought to be driven by life cycles and life events. You get married, so you want to buy a house. You move because of a job change, so you sell one home and buy another. That sort of thing. But right now, the housing market is clumsily frozen up because of elevated prices and high interest rates. People expect either elevated prices or interest rates to come down, making this a bad time to buy. It's inefficient because you don't get the kind of sorting that would improve the match between families and housing situations. Here’s a news story about how housing markets have frozen up:

Housing Market: Home Sales Plummet to Lowest in 13 Years (businessinsider.com)

The run-up in housing prices is part of a general surge in households' wealth since the pandemic. Has it been sufficiently remarked how counterintuitive and weird this is? In 2020, the pandemic seemed extremely destructive of the economy. You would think that would make stocks and housing prices crash. Instead, they surged:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/BOGZ1FL192090005Q

Figure 12

What does this mean?

First, it means that if Americans were to suddenly liquidate their stocks and houses and use them for consumption, they could consume a lot more than they could before. To avoid a fallacy of composition, since everyone couldn't actually do that at the same time without the asset prices being affected, you have to interpret this as an aggregate of options that could be exercised individually, or something, rather than as a viable collective option for everyone at the same time. But never mind. I think the point comes across. There's been a kind of surge in latent purchasing power. And some of this spilled over into booming consumer demand in 2021 and 2022, which strained supply chains and all that, until the Fed aggressively hiked rates to cool the economy off.

Second, the surge in wealth suggests hope for the future. Today's public companies and real estate will hold value over time. If the economy is future is bright, if jobs will stay abundant and productivity will increase, then it's good to grab those things now, because their prices will go up or at least stay high in future. And if you're willing to pay a lot for a house, that suggests a lot of confidence in your future wages. If you're willing to pay a lot for a stock, that suggests a lot of confidence in your future dividends. Why so much optimism? One reason is telework, which opens the door to more efficient organizations and happier lifestyles. The other is that it briefly looked like America might have gotten smarter about macroeconomic policy. I'll explain what I mean by that in a moment, after laying some explanatory groundwork.

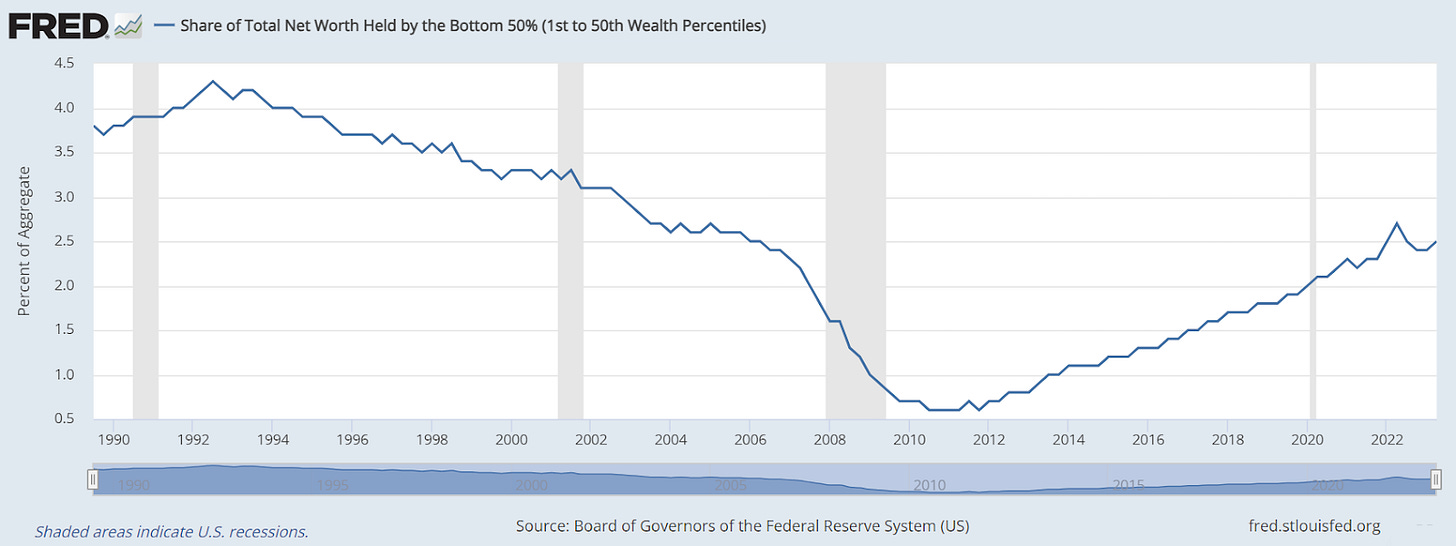

But third, this surge in wealth creates vulnerabilities, if people leverage that wealth for consumption or risky investment. We're seeing this in housing prices now: prices got bid up, and now many who might like to sell can't afford to take the losses, so markets have become troublingly illiquid. That's a fixable problem, but we're not on track to fixing it at the moment. Still, on balance, Americans' much improved balance sheets are caused for celebration, especially when you look at the bottom 50%:

Figure 11

Wow! Wow, wow, wow! What an incredible change for the better, and precisely for those who need it most! After the 2008 crisis, 50% of the population had just $400 billion in wealth between them, just over a couple thousand per person. Since then, and especially since the pandemic, that has increased tenfold! And their share of national wealth has increased too:

Figure 12

Figure 12 shows that the lower classes saw their share of the nation's wealth dwindle for decades, and then fall off a cliff in 2008. But since then, there has been steady recovery. The pandemic didn't stop it, and now the collective wealth share of the lowest net worth Americans has recovered from the damage of the 2008 crisis.

The recent release of the three-year Survey of Consumer Finances study has caused a lot of celebration, e.g., Noah Smith’s post “Great News About American Wealth.” While reading, bear in mind that the three years, 2019 to 2022, when this broad-based, accelerated growth in real wealth, this scrumptious bonanza of enrichment, was happening, affecting every demographic, was also the time when an inflationary surge like nothing since the 1970s was rippling through the American economy.

Why? I've made a few causal suggestions along the way, but much remains mysterious. How is it all connected, and what does it have to do with inflation?

To answer that, I need to turn from data to theory. Causation is the prerogative of theory to explain, a truth economists have forgotten in the cult of regression analysis over the past three decades, to their great cost. But I'll keep interweaving data, especially data about money and interest rates, into my theorizing. But before we move on, one more bit of data as a bridge. The surge in federal deficits is a huge causal factor affecting all the time series we've examined so far. It massively increased in recent years:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FYFSD

Figure 12

Since it's difficult to mention the surge in deficits shown in Figure 12 without sounding alarmist, let me say immediately that not only is the US government unlikely to exhaust investors' wllingness to lend, but if it did, the Fed could print the money needed to buy the bonds. The US government is borrowing in a currency that it controls, and that makes it mostly immune to the risks of disaster involved in excessive government borrowing. Still, to print money to buy bonds when investors won't would be a drastic step, and likely rather destabilizing, although we don't really know how, and our institutions don't have a modus operandi for that, and could screw it up in lots of ways. So I don't want to be too complacent. Fiscal policy does look pretty unsustainable right now, and trouble might be in store.

To foreshadow my conclusion, I think the deficit explosion was both wise and dysfunctional: wise on the part of Congress, given its constraints; but dysfunctional on the part of the system as a whole, because Congress was backhandedly doing the work that the Federal Reserve should have been doing. Monetary policy has been too tight for 15 years, and Congress ran deficits as a workaround, gradually at first, and then on a huge scale after Covid provided the pretext. That finally got us, in 2021-2022, the wholesome, robust boom that could have happened long before. It's awkward that Congress is doing it rather than the Fed, and we ought to simultaneously reform the Fed and shrink the deficit dramatically. At the moment, unfortunately, that doesn't seem to be in the cards. Instead, we seem to be on track for bad policy to drive us back into the Great Stagnation.

But again, I'm getting ahead of the argument. It will get more difficult because I need to explain something counterintuitive. Let me start with a parable.

WERFRIR: The Mysterious Nexus of Capitalism

Once upon a time, the werfrir flew free over the land. Sometimes it flew high, sometimes low, but always its golden scales glinted, and its great red-and-gold wings sparkled in the sun. Some feared it, and with reason, for the winds from its wings sometimes crushed houses by their force. Yet it was, on balance, a lucky beast, whose fiery breath kindled enterprise, and it made the land prosper, and gave hope even to the poorest.

But gradually voices of fear grew stronger, until the people became determined to dispose of the werfrir. And so one day, when it was flying low, they flung great hooks over its neck, and led it into a cave they had dug, at the bottom of which was a subterranean sea, on which it alighted and fell asleep. And though in the world above the fortunes of enterprise waxed and waned with the rise and fall of the sleeping werfrir as the water level shifted in that sunless sea, yet in general, people became rather slack and slothful without its fiery breath to stir them up. Enterprise dwindled, people fell into idleness and dull routines, and poverty condensed like dew from chilly, moist air, and fell upon many.

That's a gratuitously cryptic, not to say silly, way to say that we've been stuck at the Zero Lower Bound for most of the past fifteen years. But I needed to make an arcane point vivid.

"Werfrir" stands for "Wicksellian equilibrium risk-free really interest rate." And in the time series below, we can see its descent and disappearance underground:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/REAINTRATREARAT10Y

Figure 13

The flight underground of the werfrir, as shown in Figure 13, is a kind of hypothesis. Nominal interest rates are directly observable; real interest rates are a construct based on data; but the equilibrium interest rate that would bring demand and supply for loanable and investable funds into equilibrium is guesswork. I'm guessing that the downtrend in the equilibrium real interest rate that is visible in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s should have continued. But I have more evidence:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/FEDFUNDS

Figure 14

Here we see the Zero Lower Bound in the data. Before 2008, the Fed funds rate fluctuated. Then for 7 years it got stuck at zero. It should have gone lower but it can't. Because cash pays a zero nominal interest rate, financial instruments have to pay at least that much, in order to compete. Consequently, when interest rates hit zero, cash started to get hoarded:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/TOTRESNS

Figure 15

Do you begin to see what I meant with my parable of the werfrir being trapped underground? Bank loans do good. They get houses built and businesses started or expanded. They create jobs. Bank cash sitting idle at the Federal Reserve doesn't do any good. But price floors lead to surpluses. And the Zero Lower Bound is effectively a price floor on interest rates. So when the Wicksellian equilibrium risk-free real interest rate is negative, and that price floor becomes binding, the money that should have been lent get stuck on the sidelines, idle. There are surplus loanable funds. And like the sleep of the werfrir, that causes enterprise to slacken, and people to fall into idleness or dull routines.

Again, the intuition here is rather difficult. But a venture of theory to help you wrap your head around it.

The Functions of Money, and Why Money Shouldn’t Be Competitive as a Store of Value So that It Can Focus on Being a Medium of Exchange

First, about money. Money is traditionally said to have three functions: a store of value, a unit of account, and a medium of exchange. Of these, the third is the most distinctive, essential, and necessary. Without money to serve as a medium of exchange, we would be reduced to barter, with its requirement for a double coincidence of wants for trade to happen.

The extreme utility of money as a medium of exchange, especially in a complex modern economy, is backhandedly demonstrated by the way money continues to be used for exchange even during hyperinflations, when its extremely rapid loss of value causes great inconvenience and confusion. Even when restaurants have to change their prices multiple times in a day to keep up with inflation, they'd still rather price their food in money than in some real commodity like nails or candles or cigarettes. Money still functions as a medium of exchange when it has become worthless as a store of value, or as a reliable, intelligible unit of account.

Of course, hyperinflation is bad, and it's better if money is a decent store of value and a reasonably stable unit of account. It's good to spare people the laborious arithmetic of adapting to constantly changing prices. It's good if the economy doesn't have to be a game of "hot potato," and some spare cash can be kept on hand for a little while without becoming worthless.

On the other hand, money can't actually function as a store of value and a medium of exchange at the same time. When money is sitting in a safe, storing value, then it isn't being used to facilitate transactions.

And lots of other things can store value. Money is not needed for that purpose. Not only that, many other things not only store but grow value. Or if at a given time, the economy is rather poor and investment opportunities, so that ideas or how to grow value are scarce at the margins, at least many things other than money can store real value, rather than storing purchasing power and relying on other people to keep or make the things that that purchasing power will purchase. There's a sense in which the hoarder of money is dependent on the larger economy in a way that the hoarder of goods is not. If I store wheat in my basement, I can eat it when I like, with no need for help from anybody. If I store cash in my basement, or money in the bank, I'm relying on farmers and stores and warehouses to make and store goods for me, which I will purchase. Often, that's efficient. Maybe I don't have a comparative advantage in storing wheat. Maybe I have better things to do with my basement. And the stores will probably appreciate my business. But there is no natural right to keep one's idle purchasing power intact. I have an obligation not to steal wheat from your basement, but society does not have an obligation not to take away some of your purchasing power by printing more currency. Often, it's in society's interest to manage the currency so as to stabilize the purchasing power of a dollar, but sometimes it's not. Sometimes a misguided commitment to stable prices can be economically crippling.

Case in point. Let's think again about (a) all those bank reserves sitting idle at the Fed, (b) those years in which home building was slow, and (c) the recent run-up in housing prices. In retrospect, it would have been nice if all those idle excess reserves had been used to build houses instead. With household wealth recovering, jobs galore, and real wages rising, so much is wonderfully coming together to repair our broken social contract, but housing is the big missing piece. You're not really living the dream if you can get evicted at any time. So we can't feel very happy about the macroeconomic social contract if even robustly rising wages and a healthy increase in lower class Americans' net worth still leaves them unable to buy homes. So what would it have taken to mobilize all those reserves?

Low interest rates boost home building, but nominal interest rates couldn't have gotten any lower. But real interest rates could have been lower, if inflation had been higher.

And with that, we begin to glimpse the upsides of inflation.

Wage Attrition and the Labor Market Upside of Inflation

At the beginning of this post, I talked about some downsides of inflation, the big downside that it makes everyone poorer– except that it doesn't – and the small but real downsides, like "menu costs" and "shoeleather costs." Now let's talk about the upsides.

I could say that most people get more income, in the sense of more nominal dollar income. Of course, that's not a real upside. That's just money illusion.

But there are a couple of real, solid upsides of inflation. One has to do with labor markets, the other with capital markets. I'll start with labor markets.

In labor markets, inflation helps to mitigate the problem of downward nominal wage stickiness. In general, employers don't like to cut nominal wages. Generally, an employer who can't afford, or can't justify, a worker's nominal wage, would rather get rid of him all together than cut his pay. A worker whose wage has been cut will be mistrustful and disgruntled, and will probably send out resumes. He'll be bad for morale. Lay him off, and the anger goes out the door.

This seems irrational. A worker who wasn't worth $50 an hour might still be worth $40 an hour. If his outside options are poor, he might prefer to stay then get laid off. Why get upset? Yet I think it actually makes sense. When someone is hired, a rapid lock-in process takes place, whereby the job fit improves through mutual learning, while the outside options of both the worker and the employer deteriorate. There could be opportunism on both sides. If the worker demands a 20% raise, It might be worth it for the employer in the short run, rather than lose the training investment and have to go through the hiring process all over again. Likewise, a worker who had a lot of options when they accepted the job probably won't have them a few months later if his wage gets cut by 20%. Rigid arrangements help to block opportunism and let the boss and the worker focus on shared goals. That's why pay arrangements are and should be kind of stupid. You don't want to keep opening up that can of worms. That doesn't apply to every job, but it's very common for full-time positions in large organizations.

The result is that when inflation shifts, most wage rates, if nothing is done about them, just sleepwalk forward at a fixed dollar value, oblivious to the macroeconomy. So as prices rise, their real value falls. Plenty of people will get wage hikes because their employers want to retain them. But employers can nonconfrontationally let a lot of wages slide, in real terms, by just not giving raises. Mildly decreasing marginal product can lead to wage attrition rather than an inefficient layoff. Some will then jump ship, and may discover a better fit. Quits rise, layoffs fall. Moderate inflation gives employers more comfortable options for easing out the low productivity time servers.

One way to put it is that the inflation rate is the automated wage attrition rate. Automated wage attrition sounds bad. People don't like losing purchasing power just because they don't get raises. But it's usually better than getting laid off. And if you don't like it, you need to either be a bit footloose, or else be a bit more pushy about getting raises. It's hard to prove that the resulting behavior on the part of employers and workers is good for the economy. It's so subtle. But it's not hard to get the intuition of what it might be so. Pushy, footloose workers are more likely to polish their resumes, self-train for new skills, and overperform to prove their value. Employers nervous about quits will give a lot of pay raises, but probably unevenly. Inflation is bad for the organizational time servers that tend to accumulate in most organizations and drag down productivity and innovation. Smart organizations will take advantage of inflationary times by leaving the time servers out of the pay raises, and maybe they'll leave.

Again, it's subtle. But the post-pandemic labor markets, with quits far exceeding layoffs, lots and lots of job openings, real wages rising, and lots of entrepreneurship, are all suggestive of the labor market benefits of inflation. I wouldn't always recommend that. There are times when I'd recommend deflation, precisely because it would spread the wealth through automated real wage increases for all, with minimum disruption to organizations. But right now, I think an edgy labor market with a lot of churn is what we need to sort workers and motivate skill upgrades and stir up mobility and productivity growth.

But the biggest upside of inflation is in capital markets, where it can get the lazy money off the sidelines and put it to work, and awaken the werfrir from its cave.

How Inflation is Sometimes Needed to Free the Werfrir and Put Money to Productive Work

The classic supply-and-demand chart in economics is a case in point of the old saying that "a picture is worth a thousand words." If anything, I doubt that even a thousand words, or ten thousand, could deliver with so much force the intuition about how competition brings supply and demand into equilibrium. The chart is overapplied in some ways, and economists often misunderstand the economy because the ease of equilibrium analysis, once you get the hang of it, makes them constantly assume for convenience that sellers are price takers when they usually aren't. But it's underapplied too. The single most important thing to understand about inflation, and just about the most important thing to understand about macroeconomics, is almost insurmountably counterintuitive until you draw the right kind of supply-and-demand chart of the market for loanable funds, and then it suddenly becomes plain.

In the chart, SLF is the supply of loanable funds, DLF is the demand for loanable funds, and r* is the equilibrium real interest rate that makes the quantity of vulnerable funds demanded equal to quantity of loanable funds supplied. So far, all is well. Supply of loadable funds come from people who have more money than they have a good immediate use for, and who want to store purchasing power for the future. Demand for loanable funds comes from people who have good immediate uses for money and can creditably promise to pay it back in future. The market for loanable funds connects creditors and lenders for the benefit of all concerned. Projects get financed and consumption smoothing takes place. The real interest rate is the price at which present purchasing power is exchanged for future purchasing power. The higher the interest rate, the more people want to lend, and the less people want to borrow, so there is some rate at which these balance out. Every lender finds a borrower and vice versa.

But now note the Zero Lower Bound, which is equal to the negative of the inflation rate. It's quite possible for the equilibrium real interest rate to be negative, if lots of people want to transfer purchasing power to the future, but the actual prospective productivity of the future economy is looking somewhat bleak. And lending can take place at a negative real interest rate, because of inflation. But lending at negative nominal interest rates doesn't make sense, because creditors can just hoard cash instead. So there is a floor on nominal interest rates of 0%. What happens if the equilibrium real interest rate sinks below the negative of the inflation rate? Capital markets don't equilibriate. Some lending still happens, at interest rates based on 0% plus risk and liquidity premia. But a lot of money just sits idle. Remember all those surplus reserves that banks are holding at the Fed? That's what happens at the Zero Lower Bound.

It can get worse. A lot worse. Hoarding cash tends to take money out of circulation. Less money in circulation tends to cause prices to fall. Deflation. Deflation makes hoarding cash even more attractive. That means more money taken out of circulation, and more deflation. That's what happened during the Great Depression: falling prices, hoarding, bank failures, more falling prices, more hoarding, in a vicious circle, and a collapse in economic activity. It could have happened again in 2008, but the Fed prevented that. We have a pure fiat currency now, not a gold standard, so the Fed can make as much money as it likes, and be sure to avoid deflation. But the Fed only prevented the deflationary spiral. It didn't get us out of the zero lower bound trap. What the US economy suffered in the decade after 2008 was nowhere near as bad as the Great Depression, but it had the same causes and the same character. The Great Stagnation was the refrigerator to the Great Depression's freezer.

And what's the solution? More inflation. If you can just pump enough money into the economy so that the general price level starts to rise, creditors have more incentive to lend or invest. Money gets off the sidelines and starts doing productive. Things: building houses, building factories, starting businesses. Even if people can think of nothing better to do than to hoard consumer goods for raw materials, sometimes that's still better than hoarding money. It creates demand in the present and saves value for the future.

Is this fair to creditors and savers? I think a lot of people have an intuition that it isn't. Let's probe that a little bit. I think the intuition at stake here is the people have a right to the fruits of their labor. Inflation takes that away. Now, I would agree that when people build houses or grow wheat, or in any other way convert their labor into some physical good of enduring value, they have a right to it, and the justice of society is damaged if that right is violated. But when they convert such physical wealth into a currency maintained by society for the purpose of mediating exchange, they do not have a right for that currency to maintain its value. It is often in the interest of society, indeed, it is nearly always in the interests of society to some extent, that the currency should maintain most of its value in the short to medium run. But sometimes it is not in the interest of society for the currency to be a decent store of value in the long run. Currency should be mediating exchange instead of just storing value. The function of storing value should reside in capital assets and productive enterprises. So I don't think savers have a valid grievance when inflation reduces their purchasing power. They should have invested. And if macroeconomic conditions were such that no value maintaining investments were available, then it is simply too burdensome for society to keep the value of savers' savings intact, and society doesn't owe them a risk-free wealth maintenance plan.

Nonetheless, for the past generation, society has provided a risk-free wealth maintenance plan, through very low inflation, against its interest and better judgement, and the result is that savers have felt too little urgency to put their money to good use by building homes and factories and starting businesses, or funding those who do. As a result, we have fewer of the structures, businesses, and technologies that we could have had if inflation had been a little higher and forced more of people's savings to go to work. I may sound like I'm leaning in favor of debtors and against savers, but it's not so simple as that. Yes, inflation provides relief to debtors, but savers can benefit too, either in their capacity as investors, buoyed up by a faster growing economy, or as homeowners, workers or consumers. Keynes with muddle-headed in a lot of ways, but the big, consequential inside that he drove home is that unemployment, wasteful and unnecessary and avoidable unemployment, is real, and once you get that, The next thing to understand is that it's bigger than people not having jobs. Other things than people can be unemployed. People can have jobs and their skills might still be unemployed. A red-hot economy can put all the structures and skills and ideas and organizations to better use, mitigating this multi-dimensional unemployment, and that's a positive-sum game. Relief for debtors doesn't have to be offset one for one with pain for savers and creditors.

Reforming the Mission of the Federal Reserve

Don't overestimate the radicalism of what I'm saying here. I'm a million miles from wanting to overthrow capitalism. If you like, my message is as boring and unambitious as that we should aim for 4% to 5% inflation, like in the Reagan years, rather than the 2% that the Fed aims for now. At a time when almost everyone seems to be down on the political establishment, I'm praising them. By my account, Congress has been doing a good job! And while I'm more critical of the Fed, it's not really their fault. The Fed can't invent its own mission. It's a servant of the democratically elected branches of government. Some argue about what the fed code or couldn't do within the framework of its congressionally defined mandate. That's too in the weeds for me. Yet I do think the Fed is the core of the problem, like a general messing things up by fighting the last war.

The big problem is that money is too tight, and the Fed is trying to get inflation too low for the good of the economy. But if we're going to haul the Fed in for repairs, and give it a new and improved mandate, I wouldn't stop at raising the inflation target. Here's what I'd advocate.

The first priority for the Fed should be to make sure that the equilibrium risk-free nominal interest rate is always positive. Keep the werfrir flying. That's roughly equivalent to saying that US Treasuries should always offer a higher return than cash, But it's a little more complicated than that because interest rates are a whole ecology, I'm trying to manipulate a single interest rate can have perverse effects. The key is that there should be either enough good investment opportunities or else enough inflation to prevent people from wanting to hold cash as an investment.

If that is the case, as it usually is, the Fed's second priority should be sustainable asset price growth. Asset price volatility is more problematic than consumer price volatility. If consumer prices jump, you can tighten your belt a little bit. But when housing prices or stock prices surge and plunge in value, that wreaks real havoc in business and/or in people's lives. Sudden impoverishment is obviously disastrous, but sudden enrichment, too, is usually either a symptom or a cause, or both, of big problems.

If the Fed had been committed to sustainable asset price growth, by the way, it would have prevented the inflationary surge in 2021-2022 by raising interest rates as soon as housing and stock prices surged, rather than waiting for the asset price surge to feed through into consumer price inflation. But in general, sustainable asset price growth is consistent with much higher inflation than has prevailed in the past 30 years.

As a third priority, the Fed could aim for an inflation rate that would contribute to the affordability and sustainability of national and personal debts.

Finally, as a fourth priority, the Fed should keep consumer price inflation as low as possible. But only as a rather low priority. The mild inconveniences of consumer price inflation are a small price to pay to keep asset growth strong enough and real interest rates low enough to use resources thoroughly and grow the economy to its potential.

A brave new economy is possible. We got a glimpse of it in 2021-2022. Now, instead of that, we have high interest rates, a cooling, a tightening economy. Some call it a “soft landing.” But we could be flying instead.

As a final note, let’s circle back to that federal deficit, and the fiscal unsustainability of the course that the US is on. Inflation helps with that, in three ways. First, a given volume of debt, in nominal dollars, steadily shrinks in the face of inflation. If inflation is 5%, then the real burden of a debt of $X halves in 14.2 years. Second, if you want to let inflation get a little bit higher, part of the way to do that is to reduce interest rates, which also means the interest payments on the national debt become less burdensome. Don’t lean on that too much, because interest rates may subsequently increase, due to the “Fisher effect”... long story… but it might provide some relief. Finally, the big reason why the political class has felt the need to run soaring deficits over the past generation, culminating in the pandemic response, was that the macroeconomy needed stimulus. A more inflationary monetary policy would do the job of stimulating the economy, so politicians would have more room, and feel more pressure, to get back to balanced budgets.

I echo Nato's comment. I don't think I've agreed more with anything you've ever written. Great job!

Having read the second half now I’ve found more of which I’m a little more skeptical, but this comment seemed so key: “It's quite possible for the equilibrium real interest rate to be negative, if lots of people want to transfer purchasing power to the future, but the actual prospective productivity of the future economy is looking somewhat bleak.”

I think we should expect this to be common in a world with a shrinking ratio of working age to retired population. Population growth has accounted for a large fraction of all real growth for all of reliably measurable economic history. We must expect that any claims we put on the economy’s output will shrink over time as the number of workers supporting us dwindles compared to the claims accumulated by our cohort. Productivity can make this far less uncomfortable and potentially prevent declining living standards, but only if we make the most of it by, for example, making sure that we stay closer to equilibrium real interest rates and keep the economy efficient.

Also we should do more to encourage and support parenting a larger future population but that’s a whole other can of worms in terms of societal narrative besides inflation.