Golden Rule Capitalism

Why and How to Abolish the Profit Maximizing Corporation through Moral Suasion

This is a free Substack thread, and everyone is welcome to read and comment. If you can, please read and think about it and share your thoughts, because the pursuit of truth and the discernment of the right way to live is important. I will be much indebted to you for wise insights that can help me hone my understanding of things. Payment is not expected but is welcome, and will be regarded as an advance payment for future writings. Please subscribe to provide encouragement and keep engaged!

In the first post of this series, entitled "The Natural Right to Form a Corporation," I showed why corporations are legitimate and natural, typically growing out of the private promises that people make as they plan cooperation to do wholesome, productive things. Nonetheless, in this post, I will advocate the abolition, by moral suasion, of a kind of corporation widely taken today to be standard and even almost tautological: the profit-maximizing, or shareholder value maximizing, corporation. Abolishing profit maximization through moral conversion to social responsibility and altruism will help the world grow into a new, more generous, creative, productive, and edifying kind of capitalism, based on the Golden Rule.

I am not particularly or primarily advocating the abolition of profit-maximizing corporation by regulation or law. Some small regulatory nudges might be licit and helpful, but in general, law can't change people's motives, and to try to outlaw corporate selfishness would be as unjust and counterproductive as trying to outlaw private, individual selfishness. Rather, I want people to prefer not buying from, not working for, not selling to, not investing in, and above all, refusing to lead corporations that declare, and/or conduct themselves as if, their sole or primary purpose was to maximize profits. In the end, I want the profit-maximizing corporation to be left forsaken as a form of business organization, as people move on to do better things with their lives. It's very appropriate for many organizations to seek positive profits, in order to make their operations sustainable without asking for subsidies or donations, but they shouldn't seek maximum profits.

As Gerald F. Davis elucidates in his book Managed by the Markets: How Finance Re-Shaped America, the shareholder value maximizing corporation isn't some kind of eternal inevitability, but the product of a recent, ideologically-motivated, partially top-down revolution, by which corporate raiders loosely allied to free-market ideologues in the Reagan administration carried out a wave of takeovers, seizing and often splitting up or otherwise reorganizing the muddle-headed conglomerates of mid-20th century capitalism, and created a credible threat of takeover that scared most corporate managers into toeing the line of a new profit maximization-based corporate model. It wasn't Eden before (mid-20th century companies tended to be somewhat lazy and complacent) and the genie can't simply be put back in the bottle. But the hopes that shareholder value maximization would renew economic dynamism have not been vindicated, and an excursion into economic theory quickly shows why we shouldn't have expected them to. And the past proves that it's possible to run capitalist economies with a lot less profit maximization. My parable of the Bag End Apple Company, in the last post, showed how, in forming a corporation, people merely exercise their natural rights– the process needn't involve any special government privilege– but it also showed how a corporation with most of the usual features, such as joint stock, limited liability, dividends, and separation of ownership and control, can emerge without ever committing itself to any kind of profit maximization. A multifaceted campaign to cultivate more altruism and social responsibility in business is worth pursuing, and likely to succeed.

And my naive-sounding advice about how you can help to end the profit-maximizing corporation, if you have the right talents, is: become a business mastermind, whom company boards are desperate to hire as CEO, and then make it a condition for agreeing to lead companies, that they remove profit maximization and shareholder value maximization from their mission statements and corporate cultures, and embrace some altruistic mission, oriented to the common good, instead. If everyone with business ability did this, the profit-maximizing corporation would have to end, because corporations without missions oriented towards the common good would be impossible to staff properly.

The Golden Rule

Christians are taught to live by the Golden Rule of Jesus of Nazareth. One statement of it is "Do unto others as you would have them do unto you," as Jesus says in Luke 6:31. Another statement of it is in Matthew, in the Sermon on the Mount:

“So whatever you wish that others would do to you, do also to them, for this is the Law and the Prophets" [said Jesus]. (Matthew 7:12)

Another statement of it highlights its climactic importance:

Hearing that Jesus had silenced the Sadducees, the Pharisees got together. One of them, an expert in the law, tested him with this question: “Teacher, which is the greatest commandment in the Law?”

Jesus replied: “‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind.’ This is the first and greatest commandment. And the second is like it: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’ All the Law and the Prophets hang on these two commandments.” (Matthew 22:34-40)

Although Jesus's reference to "the Law and the prophets" suggests that Jesus is not innovating here but reaffirming tradition, it took the divine wisdom of Jesus to distill that sublime and crystal-clear moral conclusion from the jumble of Jewish sacred tradition. But there are scattered foreshadowings of the Golden Rule in the Old Testament, like this.

“‘Do not seek revenge or bear a grudge against anyone among your people, but love your neighbor as yourself. I am the Lord." (Leviticus 19:18)

Now, the Golden Rule can come to seem, through familiarity, like mere everyday common sense. It's wonderful as a solvent for troublesome domestic selfishness and all the frictions, frustrations, and offenses that arise from it. But the Golden Rule has more jobs than just producing happy families. The greatest deeds of heroic self-sacrifice, Horatius on the bridge and Martin Luther King in Birmingham Jail and the Dutch boy with his finger in the dike, are also best understood as expressions of it. Loving others as yourself can mean dying for them. That may be why moralists before Jesus were never audacious enough to commit themselves lucidly and boldly to the Golden Rule. And while Jesus's authority has made the human race pay lip service to the Golden Rule, few if any live up to it thoroughly in their conduct.

Matthew 22:34-40 closely resembles Luke 10:25-28, but in Luke, Jesus's interlocutor follows up by asking: "And who is my neighbor?" And that is the segue into the parable of the Good Samaritan, the point of which is precisely that anyone in trouble, even someone who hates you and regards you as their enemy, should be considered a neighbor, to be loved even as you love yourself. The Golden Rule is a mandate for leading a life of perfect universal altruism and love for all.

Nothing could contrast more starkly with the habitat assumption of economics, even if it's partly just as a simplification for clarity's sake, that people are perfectly selfish. And the market capitalist system that has organized the leading economies for over two hundred years is largely based on economics. And much of the labor force today works for companies that profess no higher goal than profit. How should Christians deal with this? In general, I believe Christians should work within the framework of capitalism to transform it into something very different, leading the way by exhortation and example, and in this post I'll try to begin to show how.

Profit Maximization and Shareholder Value Maximization

I've said what I'm for: the Golden Rule. Now I'll turn to what I'm against, but oddly enough, I have to give it two names: profit maximization, and shareholder value maximization. Depending on how you look at it, they may be the same thing, or slightly different.

"Profit maximization" is a more familiar term. But it begs the question: profit when?

Very often, there are trade-offs between profit now and profit later. Sometimes these trade-offs are a function of mere accounting, such as when to write off overdue receivables, how quickly to depreciate capital equipment, how to value products in inventory, and so forth. In other cases, the trade-offs reflect real business decisions, such as brand management, employee training, and the development and marketing of new products.

In the face of this trade-off, what does "profit maximization" mean? There's no good answer to that. If you tell a company's management to maximize profits, that doesn't help them decide the now versus later question. The best way to convert a profit stream over time into a single variable that can be maximized is by using the well-known financial concept of "present value," which discounts future profits on the basis of an interest rate or some other measure of a prevailing or relevant normal return on investment. Each future profit payment is substituted with an amount of money that, if possessed today and sensibly invested, would be equal in value to that profit payment at that time in the future.

So should managers maximize the present value of the future profit flow? That's hard to operationalize, because it's not observable and could only be calculated with the help of a lot of guesswork. What managers can do is to try to maximize the company's share price, which should, in theory, reflect a wise market judgment about the company's future profit stream. That's an observable metric. By this account, then, the intertemporally naive term "profit maximization" should be replaced by "shareholder value maximization."

If financial markets are perfectly efficient in processing all available information, and perfectly selfish in caring only about profits, then shareholder value maximization is the same as profit maximization for the long run. But if you don't believe financial markets are as efficient as that, there may be a lot of things managers could do to manipulate the current share price that aren't in the long-run interest of the company or its loyal shareholders, and other things that would pay off for the company share price in the long run, but not immediately. In principle, a manager who loves his company, or who takes his duty to loyal shareholders very seriously, might try to maximize the present value of the future profit stream instead of the short-term share price.

Also, shareholder value maximization only works as a proxy for future profits, if shareholders are pretty single-minded about valuing profits. If shareholders follow my advice in this post and try to conduct their investment behavior as an expression of the Golden Rule, they might shun merely profit-maximizing companies in favor of companies with positive social impact, and share prices would adjust accordingly. In that case, managers would maximize the share price as much by high aspirations of service as by raising profits. That would be good, but I would still urge managers to get away from any kind of profit maximization or shareholder value maximization, and reorient corporate missions towards practicing the Golden Rule.

Non-Profits, For-Profits, and Golden Rule Self-Sufficiency

Some might be inclined to suggest, if I don't like profit maximization, that after all, society already has an alternative to that. The non-profit sector is large, diverse, and thriving. Where does that fit in? Is that a solution?

Yes and no.

It's possible to imagine the non-profit sector growing and taking over, competing with and gradually crowding out private for-profit businesses. That has some appeal. In that society, there'd be a lot more fundraising, and presumably people would need to be more generous in donating to various causes to make it all work. It could happen. But that's not quite what I'm advocating for. We need to probe a few definitions to get clarity.

At bottom, what is a nonprofit? What is a for-profit? Let's consider a few defining questions that tend to distinguish them:

How do organizations fund their operations? How should they fund them?

What are organizations' missions?

What do they do with any extra money that they don't need, or just don't have a particularly good use for?

Taking these in turn:

For funding, some organizations ask people to pay them for goods and services. Some organizations ask people to donate because they believe in the organization's mission. Some organizations get money from the government.

Investment income from an endowment and bank loans are other options, though they only serve to manage a resource flow over time and need to be covered by an influx of money from donations, subsidies, or sales sooner or later.

The three basic funding sources, sales, donations and subsidies, can be combined in any way.

For a mission, some organizations claim that their goal is neither more nor less than to maximize the income and/or wealth they provide to their shareholders. Others do not claim this, and they have a wide variety of other missions, usually linked to some notion of the common good.

Finally, when they have extra money, some organizations have shareholders to whom they give any extra money for which they have no good immediate or near term use. The technical term "residual claimancy" is useful here, for shareholders notionally have a claim on any residual money that a company has after it pays all other claimants, such as workers, vendors and creditors. Other organizations lack residual claimancy. If they have extra money, it's not clear what they should do with it.

Now, in everyday use, organizations are classified as for-profit and non-profit. For-profit companies are assumed to have a profit-maximizing or shareholder value maximizing mission, while non-profits are assumed to have a public purpose and ask for charitable donations.

But clearly, those options do not exhaust the possibilities for how to combine mission, funding, and residual claimancy. It's easy to conceive of an organization that neither asks for donations nor maximizes profits. And that's how I think most of the economy ought to be run.

If your organization's purpose shouldn't be maximizing shareholder value, then what should it be? Here's where the non-profits get it right. Organizations should articulate some altruistic purpose, linked to some conception of the common good, and work for that. Only such higher purposes are fit to work for.

But just because you have an altruistic mission doesn't mean you have to ask for donations. Producing goods and services that people have a willingness and ability to pay for is quite compatible with altruistic motivations, and can make operations sustainable without bothering to look for subsidies or donations. If you have to resort to fundraising because you're helping people who can't pay, fine. But it's good to be financially self-sufficient if you can, and it's kind of tacky and troublesome to ask for, or maybe even to accept, donations, if you can cover your costs with what customers pay you. Sam and Pippin rightly had scruples about accepting gift money for their company. And you can mix commerce with philanthropy by working your organization's inspirational mission into its advertising.

Also, it's good in a way to have shareholders and well-defined residual claimancy. It's better to have a plan for what to do with excess money you may end up with than not to have a plan. It's a weakness of the non-profit model, that if they do get a windfall, it's not clear what should be done with it. Like the Bag End Apple Company, it's possible to have shareholders without promising to maximize their value.

Profit shouldn't be the ultimate goal, but it's good as a means to other ends, up to a point. Profit can fund expansion, or it can create a financial buffer to make operations sustainable in the face of setbacks. But if you end up with money you don't have a good use for, it's better to give it away to people who do have a use for it, than to simply accumulate in the coffers of an organization that doesn't need it, or to be spent by the organization on activities which are not its comparative advantage. And if you are going to give away money, it's better to avoid getting besieged by beggars by settling in advance how you'll distribute it. Enter shareholders. And I think it's okay to use the prospect of potentially benefiting from windfall profits as part of the mix when motivating people to give you money to finance your plans. All of this is compatible with altruistic motives.

"Golden Rule self-sufficiency" is one way to characterize the kind of organizations that I'm advocating for. But to give a fancy name to it risks masking the naturalness of it. Collaboration naturally gets organized around things that people agree on, and everyone should, and plenty of people do, agree on the Golden Rule. Profit maximization can never really settle because it's unnatural. It's aspirational, and it's the wrong aspiration. Instead, corporations should practice the Golden Rule by defining some aspect of the common good that they specialize in serving, and working for that, like non-profits, while also doing whatever other good they can along the way. At the same time, most of them should fund their operations by selling, rendering them organizations self-sufficient. The organizational form that I'm describing is related to the "public benefit corporation" or B-corp, and somewhat related to the "environmental, social governance" (ESG) and "stakeholder capitalism" desiderata promoted by giant investor BlackRock. Under Golden Rule capitalism, all corporations would be public benefit corporations in spirit, but ideally, they wouldn't need to call themselves that. They wouldn't call themselves anything special. They'd just remove profit maximization from their mission statements, and participate in, and be normal and respectable in the context of, a general business culture which would regard profit maximization as a vice rather than a virtue.

I think it's good that ESG and conscientious investment trends seem to be breaking up the ideology of profit maximization, and I hope they succeed. But there's a risk that corporate missions pursue the common good in ways that are too uncritical and conformist, which might only make them muddle-headed and inefficient. Far from being conformist, corporations should leverage their business experience and expertise to understand and aim at aspects of the common good that they can see more clearly than others can. They should believe in their vision of the common good enough to stand ready to offend people by their zeal to pursue and advocate for it, if others disagree or feel threatened, including defending efficiency against the arbitrary demands of "diversity, equity, and inclusion." Of course, in my view, companies' vision of the common good should above all be aligned with the great source of insight about the good life of man: Christianity. Some won't like that. But debates about the good and competitions for the moral high ground can be an excellent school of virtue. Bring it on!

So now the portrait of Golden Rule capitalism begins to take shape. It would be full of organizations which, like the corporations of today, have shareholders, and try to make profits, and don't ask for donations, but which, like the nonprofits of today, would articulate their motives in lofty, altruistic terms, aiming to serve the common good in some way. They would be full of Christians engaging in business in order to serve Christ by loving their neighbor as themselves. Altruistic missions would provide the organizations with their solidarity, and help motivate people to lead, work for, sell to, invest in, and buy from them. Everyone involved would regard their participation in corporations as managers and leaders or workers or shareholders, but even to some extent as shoppers or suppliers, as a way of doing unto others as they would be done by. Investors would use their money to fund ventures that benefited people. Workers would consciously serve not only their employers, but also their customers, investors, suppliers, and competitors. Customers would serve not only themselves but also the many other beneficiaries of the company's operations, which their custom helped to fund as well as to direct. And business leaders would organize it all with a view to achieving high productivity and just distribution and knowledge and a clean environment and the whole panoply of societal benefits that can flow from a well-run, public-spirited company.

How would shareholders be affected? Under the status quo, there are a lot of companies that will sell them shares, and then publicly promise to try to maximize the value of those shares. That seems good for investors, prima facie, though perhaps at others' expense. Well, shareholding wouldn't be abolished. Some companies would still pay regular dividends, because they found themselves inhabiting a profitable niche in the economy, and routinely had extra money to give away. Companies would still practice the Golden Rule towards shareholders, among many other stakeholders.

And while shareholders might get less ROI, if anything, I think they'd be likely to get more. Often, there are things you can do that would increase profits except that other people's profit-maximizing behavior gets in the way. Golden Rule capitalist companies would be as eager to do things that increase profits for other companies as for their own, so companies in general might well be more profitable overall, if they could all agree to be less profit-maximizing individually. We'll see some examples of that below.

Rather than regretting that companies no longer claim to work for them but for the common good instead, I would wish for shareholders to enter into the spirit of Golden Rule capitalism and not even wish to maximize individual returns, but instead, to maximize the good they could do for society by investing.

Why Altruism Raises Productivity: Proofs of Concept

So far, I've been arguing by definition and rhetoric, explaining what I mean by Golden Rule capitalism in terms that tend to heighten its appeal, rather than digging into the logic of it and supplying real, substantive argumentation for why it is right. I must admit that mere definition seems likely to be persuasive. For many, it will be simply obvious that replacing profit maximization with altruism would make for a better world.

Nonetheless, a few examples and proofs of concept of how the Golden Rule can make capitalism more productive have power to clarify and deepen such convictions immensely, while pulling the rug out from under any stubborn skeptics and handing them a burden of proof that they can't hope to discharge.

My first example I'll call the Vertical Market Game. This game features an input supplier and a consumer product maker, who purchases from the input supplier, adds value by converting them into a product ready for sale, and then sells to the public via retailers.

Each company has two strategic options. On the one hand, they can do whatever increases near-term profit. This involves raising prices, subtly reducing quality, imposing unreasonable change fees for modifications in orders, delivering late rather than working (and paying) overtime to meet deadlines, and so forth. This kind of profiteering will cause other businesses to look for alternatives, but it will take them some time to find them, so it increases profits for a while. On the other hand, the firms can focus on building their brand by creating value for all who do business with them, delivering on time, fulfilling change orders at reasonable prices or for free, adding quality upgrades, offering helpful unsolicited feedback, and generally being pleasant and profitable to do business with.

Now, it sometimes happens that financial markets value short-term profits over long-term sustainability. So here. For a given strategy by the other company, each of these companies will increase its share price by profiteering. But it will reduce the other's share price. Profiteering by the input supplier will raise costs for the consumer product maker, and reduce the reliability and quality with which it can supply retailers. Profiteering by the consumer goods maker will include playing hardball in its negotiations with the input supplier, as well as reducing ultimate consumer demand and thereby demand for the input supplier's products.

The interaction therefore takes the form of a game in which the payoffs are as shown below.

The Vertical Market Game

The third term, consumer surplus, shows how much value is created for the consumer product maker's customers. It depends on the volume of sales as well as quality and price. It is highest when both firms are brand building, so that a steady stream of high quality products is brought to market at a low price. Profiteering by either firm reduces consumer surplus by raising prices, reducing quality, and/or lowering sales.

Clearly, in this quite plausible and typical example, shareholder value maximization impoverishes both companies as well as society. The game has the form of a "prisoner's dilemma," in which cooperation is beneficial to both parties, as well as in this case the public, but is undermined by the pursuit of self-interest.

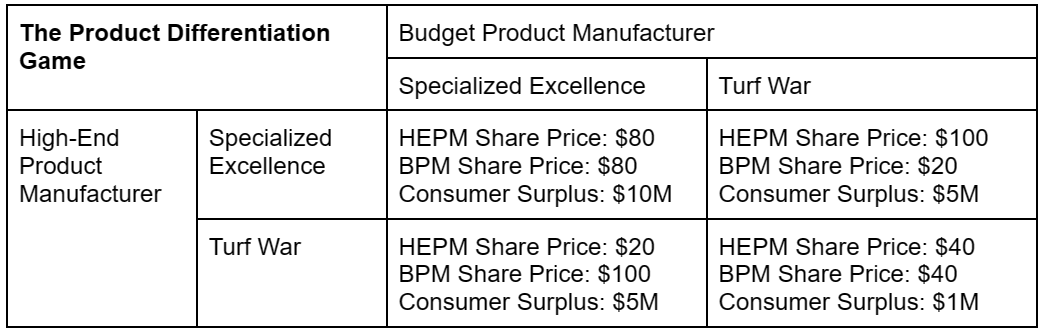

Let's take another example, which I'll call the Product Differentiation Game. In this game, two manufacturers of products in the same category, a High End Product Manufacturer (HEPM) and a Budget Product Manufacturer (BPM), have the option of differentiating their products through the pursuit of specialized excellence, or engaging in a turf war where they copy each other's product features and try to grab market share. Consumers benefit in one way from the turf war, which drives down prices, but they benefit more from product differentiation, since the differentiated products have different uses and give consumers a real improvement in selection. The payoff structure of the game is shown below.

Here again, a very typical and standard business situation takes the form of a prisoner's dilemma game, in which cooperation benefits both of the interacting parties as well as society, but is undermined by self-interest. If these firms maximize profits, the bad outcome will occur. If they do something different, and especially if they serve the common good, the cooperative outcome will be achieved, which is better for all.

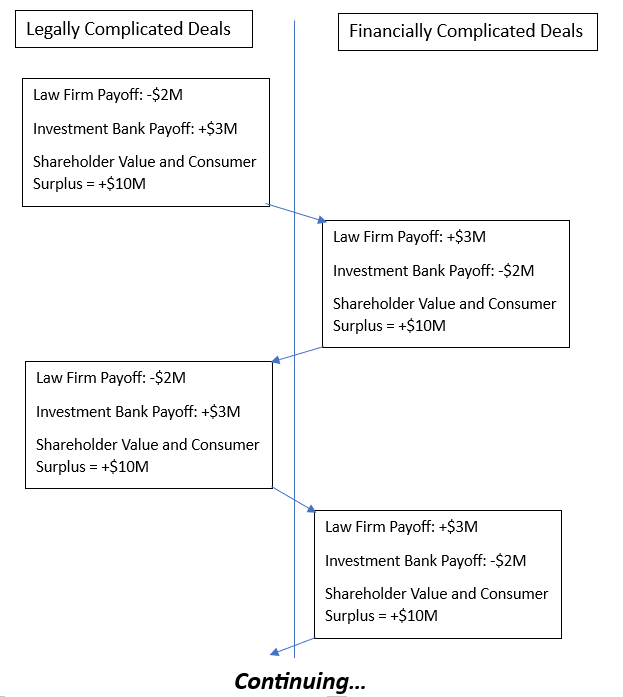

One more example. A law firm and an investment bank have been cooperating for years to help broker mergers and acquisitions. The M&A business is troublesome, full of uncertainties, tough negotiations, and regulatory tripwires, but it's quite lucrative on average, sometimes spectacularly so. Better yet, it's widely recognized in the business community that this particular pair of big business matchmakers has regularly midwifed durable, well-run companies, a legacy to be proud of. Still, any given deal is as likely as not to be a loser for one company or the other, as legal or financial complications turn into a time sink.

They need each other. Neither company can do an M&A deal by itself, and to build a similar relationship of trust with another partner would take years, if other suitable partners exist at all, which isn't clear. On any given deal, both firms usually have a pretty good hunch whether they're going to come out ahead or not, but to restructure compensation to more accurately reflect level of effort would add yet another dimension of complexity to a process that's already on the verge of exploding through being too complicated for the needed parties to understand. Also, by the time they've got far enough to guess their costs, they'll have signed a lot of NDAs and whatnot, so that their decision will be interpreted as a signal of deal quality to outsiders who haven't signed the NDAs and seen the confidential information. That would tend to alienate potential M&A clients and spoil the business. So instead of renegotiating or being choosy, the two partners just take the losses for the sake of the partnership. There's a vague MOU which obliges each firm to hold up its end in the continuing deal stream, but either party can exit at any time.

This arrangement continues for years, until leadership changes at the top of both firms cast doubt on its future. The two new executives assign analysts to track the past costs and revenues from the M&A business and then extrapolate into the future. The analysts summarize the firms' relationship as a game of the following form:

In other words, there's basically an alternating stream of deals, where each firm tends to lose two million bucks on one deal and then make three million bucks on the next. It's a good line of business if both firms keep playing along, but could turn out badly if the other firm chooses to exit when its turn to take a loss comes. What are the odds of that? Well, it depends on the caprice of the two bosses.

Let's suppose there's a probability P that each boss will exit the game at any given turn where his firm is due to take a loss. It turns out that the expected future profit stream, on the threshold of one of the losses, assuming that one's own firm stays in but the partner may exit, is… implying that the firms should stay in if P is greater than ⅔.

But it's quite possible that P will be estimated at less than ⅔, and then something rather unfortunate happens. Both firms would rather continue the relationship, but each exits, because they're not willing to risk the other firm exiting at a bad time. And the beneficial mergers cease for lack of brokers to arrange them.

Here again, altruistic motives can solve the problem. If the firms don't make it their goal to maximize profits, but follow the Golden Rule, valuing the welfare of others as much as their own, then they'll keep doing good work, and they'll make more money, too.

Situations like these, where the Golden Rule yields a better result than selfishness for all concerned, could be multiplied endlessly, and I think they're very common in business, as they are in personal life. It would be very hard to prove this with data, however. It's very hard to prove with data even that firms' share prices depend on their decisions at all. Causation depends on counterfactuals, but data doesn't contain the counterfactuals.

Reinventing Economics

Now it's time for some careful reasoning about the epistemic next steps in light of these proofs of concept.

First, what do these proofs of concept prove? They prove that there are multiple plausibly typical scenarios in which shareholder value maximization makes everyone worse off.

Second, how can we generalize from these scenarios? Are these sorts of situations very common and important, or are they special exceptions to a rule? The lazy answer is to ask what the "data" say, and if data are lacking to prove the abundance of situations where altruism raises productivity, to fall back on conventional economic theory, which for no better reason than convenience has traditionally assumed that firms are profit maximizing, there is perfect competition, and markets are efficient.

We need to do better than that.

"Data" is, in fact, a very crude and limited instrument by which to understand the world. The most essential features of most interesting and important situations are not quantifiable in a routine way. Motives are not observable. Counterfactuals are not observable. But every human being has an ability to perceive motives, certainly their own and usually those of others, and to imagine counterfections, and to that extent is wiser than the "data." Don't get me wrong, I love data! Pulling lots of data tables, running statistics and crosstabs, recognizing patterns and turning them into persuasive visuals, and occasionally getting multi-dimensional and running a regression or two, yields new, true, and useful propositions with impressive frequency. But generalization is the prerogative of theory, it takes a lot of theoretical acumen to interpret data competently, and theory can cover a lot of ground just by reasoning from casual experience and common knowledge, if it's allowed to do so, before any formal "data" gets drawn in. If theory is constantly interrupted by thoughtless demands for data, it can't develop properly, and empirics as well as theory before stultified and futile. Economics has been laid waste for 30 years by people overvaluing data and overindulging a gratuitous and naive skepticism about intuition, common sense and reasoning from everyday experience. We need to break free of that.

So third, while being alert for natural experiments that might happen to shed additional light, it's essential to have enough common sense to realize that proofs of concept like the above have tremendous prima facie generality, whereas the contrary assumption that selfish behavior yields Pareto-optimal outcomes was always based on arbitrarily adopting implausible assumptions and never had any real authority. So we should jump to the presumptive conclusion that altruism raises productivity, and let the burden of proof shift to those who would deny it.

Now, economists have a funny habit of assuming that individuals are narrowly selfish and governments are infinitely altruistic. Oddly enough, these assumptions do not spring from statist bias. It's comparable, rather, to a boastful boxer who challenges an opponent while offering to tie both hands behind his back. Economists tend to claim expertise in the operations of markets, and to be apologists for their beneficence, up to a point. But one soon discovers that there are a lot of "market failures," where the highly restrictive assumptions that yield conclusions about market efficiency don't apply, and then the economists plunge into a quagmire of quixotic interventionism, recommending all sorts of theoretically beneficent policies that demand tremendous public-spirited altruism on the part of government, as well as tremendous competence and skill, to be carried out. And then governments disappoint.

It's far more realistic to recognize that private actors are often moral and altruistic, and are open to being rendered more so through moral suasion, while governments are staffed with ordinary, self-interested people, who are often led by their self-interest to be lazy, corrupt, or both. If that rather commonsensical insight were followed through, it would lead to a completely different economics.

That's the kind of economics that I want to preach, and practice. That's the kind of economics that's fit for Golden Rule capitalism.

How to Be an Effective Altruist and Work to Achieve Golden Rule Capitalism

One purpose of this post is to inspire young people of talent to become business leaders.

I never thought about trying to become a business leader when I was a kid, and the widespread notion of business leaders as soulless greed machines was a big factor in my lack of interest. I didn't want to make a lot of money, and I didn't want to hang out with people who wanted to make a lot of money, so I didn't pursue business as a career.

Now I kind of regret that I haven't led my life so as to have the knowledge, the resume and the connections that might have enabled me to become a CEO. Well-run businesses can do a whole lot of good, leading a corporation would be a fascinating challenge, and by now, I'm quite convinced that our society has a lot less business talent in play than it would need in order to live up to its potential.

Also, as I elucidated in the last post, corporate power is much more legitimate, consent-based, and morally immaculate than the coercive power of governments.

Still, it would be too stultifying and uninspiring to work for no higher cause than one corporation's profit. And corporations have too much power and wealth to do that without guilt. As the Spider-Man motto puts it, "with great power comes great responsibility."

Every system has hierarchies and decision makers, and leaders have disproportionate power to shape the mix of good and bad that the system does. The doctrine of shareholder value maximization holds that, in contemporary capitalism, the most important decision makers should work directly only for the interests of certain owners of certain financial instruments. That's wrong. They shouldn't. So how should Christians, or others who for whatever reason believe in the Golden Rule, and who have sufficient business talent to lead companies, deal with this situation?

As a kid, I didn't actually think businessmen were the soulless greed machines that they are represented to be in economic theory, and a lot of fiction, and some journalism. But the caricature colored my perceptions of people in business that I knew, and bounded the possibilities I imagined for the businessman's role, so that it didn't really seem possible to combine business as an occupation with a zealous effort to live by the Sermon on the Mount. I still think that working for no other purpose than maximizing profit or shareholder value for a company isn't really compatible with the Christian vocation or defensible as a way of living by the Golden v Rule. At the same time, corporations are dazzling engines of productivity, on whom modern economies, living standards, and the best hope to end world poverty depend. It would be nice to help out with that. Is there a way to do that without committing to the goal of profit maximization?

Helping out is easy, sort of. Corporations are hiring all the time. Get a job. And it's not as if they make you take an oath to make it your overriding purpose to maximize their profits in return for giving you a job. However, you do have to follow orders, more or less, and the orders will usually be aligned with profit maximization, more or less, and may sometimes be contrary to the public interest, perhaps in ways that you can't see. Generally, the higher up you go, the more discretion you will have in how you do your job, and the more influence you will have over how others do their jobs, and the more visibility you will have into the company's overall social impact, and the more you will contribute to the company's overall productivity. To that extent, it's good to be ambitious. It's good to rise. But what's the price of that? Will you become progressively more corrupted by the profit maximization goal? That's a risk. The general risk will take a specific and personal form when your company is on track to do something that you feel is bad, and to take a stand against it is to risk professional ruin. Be prepared!

Far be it from me to make any assurances that taking a conscientious stand will always work out well as far as your success in this world goes! Sometimes you will fall, and if you've risen far, it's a long way down. It's not in having the perks of worldly success, the money and power and respect and security, and the interesting and impactful work, that people get corrupted, but by becoming addicted to it. You have to be ready to lose it at any time for the sake of doing the right thing. In general, you're never really doing the right thing unless you almost don't care whether it leads to prosperity or ruin for yourself, because you care so much about doing the right thing.

The forms that the challenge of the conscientious businessperson can take are as manifold as all the subtleties of business and corporate decision making. Often, it will involve steering the conversation in a meeting in a way that powerful people don't like, saying things that they don't want said. Often, it will involve generosity in negotiations. Sometimes inspirational rhetoric will help an organization to outgrow a narrow profit focus, but maybe just as often, the challenge will be the opposite, to put on the green eyeshades and scrutinize the bottom line to make a beneficent workstream financially sustainable. Sometimes it's good to get footloose by cultivating a broad range of marketable skills, to make it more feasible to exit from a morally compromised company if a gamble to change it from within fails. But in other cases, that's precisely where the temptation lies, and signaling loyalty will enable a company to launch projects but maximize the social value of your skills. Most of the time, the actions of individuals and companies won't make their motives clear, and the most altruistic actions will have some plausible pretext of self-interest or corporate interest, while the greediest and most destructive actions can be justified by some plausible appeal to the common good. It all depends. And it's all very subtle. That's one reason why Jesus taught us to judge not that ye be not judged. There's usually a lot of uncertainty around why people do what they do. Sometimes even our own motives are hard for us to discern. But that's just why trying to practice Golden Rule capitalism such a fascinating challenge, such a school of virtue, so fit to make one's life interesting and fun and exciting, a story worth telling.

And the uncertainty isn't infinite. If you've read a lot of good novels, you'll know that while they can have a lot of moral complexity, usually by the end the verdict becomes clear: good or evil, honor or shame. Each character shines, their apparent flaws justified or redeemed, or fails, their virtues proving hollow or their purposes futile. Life is a little like that. If you pay closer attention and judge wisely, you can often get a pretty good idea whether someone's choices and traits are for good or ill. In the biographies and legacies of past businesspeople, I think you can distinguish some who definitely added huge value and created benefits that rippled outward to touch multitudes, e.g., Henry Ford, Bill Gates, or lesser-known figures like Mervin Kelly who led Bell Labs in its heyday when it developed the transistor and other technologies critical to the ICT revolution of the late 20th century, to computers and the internet. Others seem to have added little value or done damage, polluting the environment or inflating financial bubbles or inducing the federal government to back coups abroad. Usually, when business does good, it has something to do with altruism, and when it does evil, it has something to do with profit maximization.

It's easy to create abstract scenarios where profit maximization leads straight to moral disaster. The boss at Company A thinks he can raise profits if he assassinates the boss of company B, a competitor, and that he can do it without getting caught. Profit maximization says: Kill! Of course, that's a reductio ad absurdum, and any normal businessperson will assume such things are beyond the pale. But it shows the need for moral restraints, and once you let ethics in the door, where do you draw the line? What if you're polluting the air and sea? What if you're trading with dictators and rogue states, and thereby helping to entrench them in power? What if you're using political donations to sway legislators' votes? What if you're selling unhealthy, addictive products? What if you're recruiting workers into dead-end jobs, who may not realize that other jobs available to them would provide more upward income mobility? What if you're out-competing another firm by mimicking, for free, methods and technologies that it developed at great cost? There are all sorts of business practices which, without being clearly criminal, yet are morally questionable, and which a subtle and demanding conscience will oblige a person to avoid. And beyond that, there are many other good things you can do that clearly serve the common good, but may risk hurting the bottom line. Profit in the service of sustainability has some claim to be an end worth serving, but it's only one among many. Maximization gives it too much weight. There are so many other things worth working for, which should be added into the mix.

With that in mind, let's circle back to the career path of an aspiring businessperson. I have said that it's good to be ambitious. But I've also said that it's important not to let one's motives tamely align with the stated or presumed motive of commercial companies to maximize shareholder value or profit. Is there an inconsistency here? Will companies promote , or even retain, staff who are not willing to work to maximize their profit?

There are three or four reasons why I'm confident that they sometimes will.

First, by mistake. Sometimes a company will simply err in thinking that you'll work to maximize their profits, when really you won't. Don't cause them to make this mistake by telling any lies! Lying is wrong. But I've never heard of a company asking an individual point blank whether they intend to work to maximize its profits. From an operational perspective, profit maximization is more likely to lean in as a lazy presumption than to be proclaimed and enforced as a doctrine. And that should enable idealistic business people to join up, fit in, perform, and rise without either proclaiming or disclaiming lofty common good motives. Lying is probably not necessary.

Second, by outperforming others enough to win a margin of tolerance for eccentric idealism. Supposed to work or a manager put, if they worked only to increase the company's profits, raise profit by $50,000, but since they believe in practicing the golden rule towards all, they're not willing to do that. Instead, they'll work so as to raise the company's profits by $20,000, while generating $100,000 of surplus for others outside the company. Will the company employ this worker or manager? If the company is goal is to maximize profits, then they will. Of course, if they could replace the worker or manager with someone equally productive, and asking no more in wages, but willing to work solely for the company's profit, they would do that. But if you can be better than others, so that no one available could do the job as well, It gives you a certain bargaining power that can be used to turn a company towards the good.

Third, because public idealism can allay suspicions of private self-interest. Every organization requires its members to some extent to check self-interest at the door. It's impossible to organize it so that corporate interest and self-interest are always aligned. I think it comes fairly naturally to people to fall in with common goals and conventional ways of doing things, but there's always a risk that people shirk, undercut each other, engage in turf wars, leak sensitive information to the public, or otherwise betray the organization's interests.

And fourth, by appealing to and aligning with the idealism and altruism of others. I suspect that a silent majority of the real participants in capitalism sympathize more with altruism than with profit maximization, but somehow they've all been tricked into putting on the mask of an ugly doctrine. What would happen if, whenever talk of profit maximization rears its head, you interrupt and overwhelm it with generous idealism, advocating for high principles and generosity and the public interest? You just might get away with it, or better!

If you rise all the way to the top, and become a major corporate CEO, what duties do you owe to shareholders? It depends on what you promised, and maybe a little on the law, and a little on expectations. Some conformity to norms and traditions is mere justice, and you'd probably be in the wrong if, entrusted to lead a company, you gratuitously bankrupt it by giving all its assets to the poor. If you have better things to do than to maximize profits, you'd probably better find ways to proclaim and demonstrate that, to minimize the risk of lying. I don't know how dangerous that would be, professionally speaking. I think you might get away with more than you think, but maybe you'd court lawsuits. Never mind. It's more important to do what is right than to obey the law.

While I think there is a very disproportionate role that must be played by business leaders in turning the ships of big business away from profit maximization towards the common good, the rest of us can help, too.

Workers can help by most, first of all by working for nonprofits if they can, and by being selective, when job seeking, on the basis of company mission and culture, shunning companies where profit is both the official mission and the actual animating force, but working eagerly and well for companies where service and the pursuit of excellence is the top priority. Then, on the job, try to discern whether your role and tasks support the common good or just the profits of your company. If you can influence management, praise them when their decisions seem to enhance the company's contributions to the common good, and risk pushing back when they don't. If you're not sure, ask. If your company is doing good work, be loyal, and offer inspirational thoughts to your colleagues about the good you're doing. It it's not, either start sending out resumes, or take some risks to change the direction of the company.

One of the things public opinion can do is to approve and praise people who do socially useful jobs and NOT mere "gainful employment" per se. How would you treat (a) an organizational time server at a company with a lot of deceptive and exploitative business practices, versus (b) someone who's unemployed because they were that organizational time server but then distinguished themselves by speaking out against it. Bear in mind that you probably won't know much about the reasons for joblessness. If you would be more favorable to the organizational time server because they're "gainfully employed," then you're part of the problem.

Conscientious shopping can help. It's good to try to know something about the companies you buy from. Boycott if there's gross misconduct or the company's culture seems icky. Pay premiums if need be to buy from companies that are virtuous. Your shopping dollars are a vote for the kind of capitalism you want. Still, it's hard to find the time for that.

As for,you own $20,000 worth of stock, it's probably not worth your time to look into how it's invested. Just diversify and let it grow. But if you own $1,000,000, and you don't scrutinize your portfolio and make some effort to purge it of bad companies, you're probably guilty of some serious indirect sins due to bad things that companies have done for the sake of maximizing value for you. You'd better keep an eye on them and change your investments if one of your invested companies seems to be harmful for the world.

Businesses can also help by being discriminating about which other businesses they do business with. Deal eagerly with altruistic, common good-oriented companies, and shun the greedy ones.

A more productive, edifying, wholesome, generous and moral capitalism is possible. If it seems hard to imagine, so did, long ago, a world without slavery, and a world without polygamy. A world in which even powerful men have no slaves and only one wife must once have seemed as impractical and contrary to human nature as Golden Rule capitalism does today. And while its achievement is remote, the striving for it can begin anywhere, anytime. You can start thinking today about how to better align your livelihood and career path and job performance, your shopping and investing, and your opinions about companies and products and people, with the Golden Rule.

Golden Rule Capitalism vs. The Ideology of Competition

In some ways, I think the path to Golden Rule capitalism is smooth and without obstacles, although uphill. It's always difficult to set self-interest aside and focus on serving others. But movement in the right direction is easy to justify if the will is there. A company that treats its workers well can justify it as an investment in employee loyalty and morale, and not challenge profit maximization directly. Likewise, generosity towards customers and suppliers could be a way to keep them happy so they'll keep doing business. And efforts to address externalities can be represented as ways to fend off regulators or improve the company's public image, with benefits for sales and the hiring brand. You can move away from profit maximization in the name of profit maximization if need be, then gradually stop talking about it.

But there is one relevant group to whom it would really go against the grain to practice the Golden Rule in any way: COMPETITORS.

People have a propensity to tribalism. Any grouping of people, however accidental or arbitrary, will soon give rise to feelings of us versus them, we're right, we're better, etc. This instinct has fueled wars from time immemorial, leading to much courage and glory, but of course also much cruelty and injustice, sorrow and waste. Modern civilization has far less war, but channels tribal instincts in other ways. People root for their sports teams, and their companies. Yankees vs. Dodgers. Coke vs. Pepsi. Apple vs. Microsoft. One could half-jokingly tell the parable of the Good Samaritan today with a Coke manager playing the role of Good Samaritan to a Pepsi manager wounded in the roadside. Half-jokingly, because these commercial rivalries aren't so deep and serious as the old national and religious hatreds. But intelligibly, because the us-versus-them feelings to which commercial competition gives rise are a barrier to love.

But companies' non-practicing of the Golden Rule vis-a-vis competitors isn't just a function of humans' instinctive tribalism. It's built into both the culture of contemporary capitalism and the laws that regulate it.

Early in this post, I blamed the rise of the shareholder value maximizing corporation partly on "free market ideologues." In so doing, I didn't mean to cast aspersions against free market ideologues in general. I'm a kind of free market ideologue myself! But free market ideology sometimes takes a serious wrong turn. A very crude but not wholly false summary of much of the economics might run like this:

"So you want big government to intervene and make things better. All right, let's assume the worst of private markets. Let's assume they're comprised exclusively of heartless, greedy individuals and companies. And let's assume the best of government. Let it be wise and all seeing, and totally altruistic and concerned with the public welfare. Even then, we can prove that no government intervention is the best of all possible words, because everything that a wise and beneficent government can do will be accomplished by competitive markets instead. So there!"

Well, no, not really.

First, as discussed above, this kind of theory only works with some very restrictive assumptions that are not true. If you relax the assumptions in the direction of realism at all, then lots of cases emerge in which a wise and altruistic government will bring about better outcomes than a purely decentralized competitive free market system. But in the real world, where private actors are often moral and generous and government actors are often myopic, lazy, biased and/or self-serving, moral suasion rather than law and bureaucracy is often the best response to market failure. But private altruistic impulses are often stopped in their tracks by the pressure of market competition. "We'd like to do the right thing, but the competition would drive us out of business if we did!" is a common situation for companies to find themselves in.

To see what I mean, suppose your firm has some business practices that seem to violate the Golden Rule. Maybe you advertise in misleading ways. Maybe you exploit workers, trapping them in dead end jobs where they gain no transferable skills and miss out on upward income mobility. Maybe you exploit the financial naivete of the poor by selling them products they can't afford with financing that leaves them into ruinous debt. And so forth. You would like to stop, but if you're in a highly competitive industry, you may find that you cannot. The shady business practices make money. Doing the right thing would mean charging a little more to customers or paying a little less to investors. But the customers won't pay more, because they can get a deal from your competitors. Shareholders won't accept less, because they can invest in so many other firms. So you're stuck on a treadmill of shady business practices, and you can't stop.

What should happen in these cases? A good solution is for the companies to get together, talk about it, and make a deal that they'll all end the bad although profitable business practice. And that makes it affordable. "If the competition treats its workers fairly, cleans up its pollution, ends exploitative financing or misleading advertising, we can too. They'll have to pass the extra costs on to customers, and that gives us a little breathing room for the price increases we need." Firms should collude to do the right thing.

Unfortunately, that would probably be illegal.

For over a century, antitrust rules in the US and other leading capitalist countries have sought to prohibit monopoly and make the economy more competitive by breaking up certain big firms and prohibiting certain mergers. It's an interesting case of government intervention that in sense is in the service of free market ideology, trying to make the economy conform more closely to the paradigm of competitive market capitalism. Today, a company that sought to practice the Golden Rule towards competitors would attract a lot of suspicion, and many practical means of doing this, such as by limiting price competition, would be deemed illegal.

Now, there's a natural law case against antitrust. A big firm that dominates a product category, or two, or ten, thanks to its economies of scale and good reputation, is a great system of voluntary consent, from the workers to the consumers to the shareholders to the managers to the input, suppliers, etc. So is a system of ten or twenty companies that collude to set prices or define non-overlapping territories. By what right does government barge in and break up these voluntary arrangements? But I wouldn't put too much emphasis on this. Large firms typically rely on government to serve as a third party arbitrator in securing their very complex property claims against others, so it's fair for governments, in return, to have a certain say in their structure, and to bring to bear their insights about the common good. But whatever degree of right the government may have to intervene in the structure of big business, I would question whether making industry more competitive is a good use of this influence. For as we have seen, it is often precisely competition that prevents business from doing the right thing.

To come at it from another side, suppose we want some great thing to be done for the common good, which can't be self-financing: charity for the poor, patronage of the arts and sciences, the building of a bridge or a church, or in many cases, the invention and commercialization of a new technology. One of the most innocent ways to fund such ventures is for a company that has some market power and ample profit to divert some of its cash flow into the project or program that the public needs or wants. That happens all the time. The picture below displays a local example. My local supermarket has some pricing power, and apparently uses some of its profit to fight hunger in the area. But we need a lot more of this sort of thing.

It's better for common good projects to be financed by corporations than by tax dollars and government, because companies' revenues come from voluntary sources, whereas the government has to use coercion. It's not that taxation is theft, exactly, but its legitimacy is a lot more questionable. But for companies to fund big projects for the public good, they need to have good profit margins. To break up big companies or collusive arrangements in order to social-engineer a highly competitive economy greatly undermines one of the best, most innocent options for funding public goods. And big companies, if given the chance, are likely to be smarter about it than government, too. More innovative and efficient. Less bureaucratic. Corporations can't be expected to fund universal social safety net programs, though they can fight poverty by keeping certain wages high and certain prices low. But they have a big advantage over government when it comes to serving the public good in creative and visionary ways, or in diverse and opportunistic ways.

In some ways, our society is schizophrenic. We talk about free markets, but when the verdict of the market crowns one firm as the overwhelming market leader, we sometimes decapitate that firm and split it up into many. We deplore "consumerism," and yet we engage in aggressive regulation in social engineering to prevent businesses from colluding or uniting in ways that cause any uptick and consumer prices, even if the consumers in question can easily afford the price increase, and even if the increased revenue would go to a good cause, such as raising workers' wages or funding technological progress. We are especially schizophrenic about monopoly. When consumers vote for it with their wallets, government barges in to break it up by force, and yet government also enforces monopoly through the ever-expanding tentacles of the intellectual property regime, disallowing the use of patented, inventions and copyrighted art for any but the copyright or patent owner or their licensees, who may be impossible to trace. Our society needs the concept of consensual monopoly. Sometimes one efficient seller with economies of scale, a good company culture and a loose accountability to public opinion, is better than a lot of small hustlers hotly competing in a game of survival of the greediest. Yet antitrust and IP both have their rationales in a worldview that assumes government is altruistic and corporations are selfish, and that that to some extent makes that grim assumption into a self-fulfilling prophecy through law, policy, and culture.

The ideology of competition gets in the way as soon as you try to define a higher purpose for any commercial company. Let's take car company X as an example. Consider the two following mission statements:

Our goal is to meet the transportation deeds of individuals, families, and businesses, but high quality, comfortable, affordable cars, while dealing justly and beneficently with all those we transact with and positively impacting the welfare of society by every means available. (Altruistic)

Our goal is to maximize the wealth of company X shareholders by raising our share price as high as possible. (Profit maximizing)

Now, there's a lot of alignment between what the company will do based on these mission statements. Generally speaking, the company will raise share prices by making a lot of good cars and meeting a lot of transportation needs. The altruistic mission would tend to steer the company away from raising profits through deceptive advertising or exploitative financing, which the profit maximizing mission might encourage, but consumers are reasonably savvy and you probably do better, most of the time, by helping them than by trying to fool them. Just dealings with workers and suppliers, likewise, might be motivated by altruism or by a desire to pertain workers and keep supply chains healthy.

The big divergence involves competitors. The altruistic mission makes competitors like car company Y into allies. They, too, are trying to meet transportation needs. The shared mission counteracts natural tribalism. The prophet maximizing mission makes car company Y the enemy. More sales for them means less sales for us. But it's very likely that the car companies can do more to meet transportation needs. If they cooperate then if they try to defeat and undermine and sabotage each other.

Above all, knowledge sharing will help both companies do their jobs better. The worst thing that the ideology of competition does is to enshroud innovation in secrecy. The pursuit of ideas is like lighting candles: I teach you, you have light, but I am not darkened. We need more of that. But if I've invested heavily in learning something important for production and commerce, and you are my competitor, It might ruin me to let you use my ideas for free. This is the problem that intellectual property regimes are meant to solve, but the inevitably do so in bureaucratic, inefficient, and rather arbitrary ways. You can't patent to failed experiment. You can't patent a half-developed research program. And there will be huge uncertainty about a patent office's decisions in all sorts of edge cases. So competition will be a motive for secrecy in all sorts of situations, a major impediment to the free flow of ideas that nurtures technological progress. Often, the solution to this is less competition. Monopolies are often the best innovators, and it's clear why: they stand to capture the benefits of innovation, rather than being free ridden into ruin by idea-stealing competitors. A very unfortunate feature of contemporary capitalism is that engineers and inventors who would love nothing more than a free flow of ideas are constantly forced to sign horrible NDAs in order to get companies to fund their research. It's a huge burden on the productivity of innovative effort.

The historic zenith of innovation occurred in the decades before and just after big business got shackled by antitrust. Joseph Schumpeter, widely recognized as one of the greatest theorists of capitalist innovation, Saw the aversion of English speaking democracies to monopoly as little better than a superstition, a bias with historical roots, highly maladapted to running advanced capitalism. He disdained the idea that monopolists were lazy and static, having seen that they were innovation drivers because they knew the next big innovation could dethrone them if they didn't discover and implement it first. He had little use for the petty competition that whittles away profit margins to get a slightly better deal for consumers. He was focused on the grand, world-changing competition, the "creative destruction" of fundamental technological change, the champions of which are usually either quasi-monopolies already, or on track to become so. The Gilded Age gave us automobiles and airplanes and electrification and mass production and telephones and plastics and bulldozers and the skyscrapers and radio and TV and nuclear power. Since then, we've got computers, cell phones, and the internet, all born in the laboratories of giant monopolist AT&T, and microwave ovens, and space flight, and quite a few advances in medicine, I think. But we were doing a lot better before antitrust came along.

I question the justice of antitrust. I doubt the right of a government to simply break up a corporation. A corporation is a great system of voluntary consent. Where does the government get the right to say no to that? It's freedom of association. On the other hand, corporations do require an unusually sophisticated kind of protection from the government for their highly elaborated and somewhat counterintuitive property rights. It's fair to demand special kinds of accountability in return for that. I would recommend a strong push for corporate transparency. If corporations want the government protect their highly elaborate property rights and enforce their highly elaborate contracts, they should be required to let the broad public seem much more about how they do business and what they're working on, about their finances, their HR practices, their transactions, and their research. They might be more willing to share that if they weren't concerned about being forcibly broken up, and if they could mitigate competitive pressures through gentleman's agreements with rival firms.

Meanwhile, at least in some cases, I would urge business to practice civil disobedience against the antitrust regime. I would urge businesses to do what they need to do to cooperate for the common good, even sometimes in open defiance of the law, and be prepared to pay the price in a fight for the moral high ground against the Department of Justice and the antitrust regime. Try to imagine the CEO of a Fortune 500 company going to jail, and telling the cameraman as the cops hauled him away:

"Look, we could see that we weren't doing right by our workers, paying them lousy wages for dead end jobs. But we couldn't afford to treat them better because we were all stuck on this treadmill of competition. So we got together with the other big players in the industry and agreed to raise prices for consumers so that we could earn enough revenue pay a living wage to our workforce, and give them some training and education opportunities. I'm sorry the Department of Justice didn't like that. But it was the right thing to do, and if I have to go to jail to prove that, so be it!"

Wouldn't that be glorious? If I saw that, I'd start to feel like Golden Rule capitalism had arrived.

Conclusions

So that's my manifesto for Golden Rule capitalism. It's not primarily a public policy program, although by leveraging its manifold interactions with corporations to incentivize them to turn from profit maximization towards the service of the common good, government probably could accelerate a trend towards more altruism in business. But I doubt that this top-down approach could accomplish anything good without a bottom-up movement for altruism in business to accompany it. It would only foster elaborate hypocrisy. If businesses don't want to move past profit maximization, regulators can't force them, but will only make them pursue profit in more inefficient and opaque ways. Ultimately, though, it makes all the sense in the world to require less taxes from, tolerate more monopolization or collusion by, and be more ready to protect the patents of, a company animated by high-minded and visionary service to the public interest and abundant in creative and effective philanthropy, compared to one that complacently pumps out dividends to shareholders and does nothing more.

No doubt Golden Rule capitalism is rather quixotic, but it's good to have high ideals to work for. Even now, we have more of it than is generally recognized. Corporations are better than economic theory presents them. We should recognize that, honor it, cultivate it, and demand more. Public opinion can do a lot of good work. Individual striving can do more. For Christians, I think this is how you can participate in capitalism while being innocent in the eyes of God. If you resolutely strive to follow the Golden Rule in your workdays and your career path and your investment portfolio, making sacrifices and taking risks to avoid complicity in corporate greed and to turn organizations in small or large ways in the direction of altruism and service, you can look forward to your reward at Judgment Day. And secular idealists shouldn't leave Golden Rule capitalism out of their plans for a better world.

![Managed by the Markets: How Finance Re-Shaped America by [Gerald F. Davis] Managed by the Markets: How Finance Re-Shaped America by [Gerald F. Davis]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!KoL4!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa8c03173-0114-4ad3-874f-7abc14d08e45_334x500.jpeg)

The question becomes, "How close do market processes approach the effects of the Golden Rule?" Think of how to apply Vernon Smith's price equilibrium models given a free and open bidding market which invariably showed that prices tend to approach the competitive equilibrium in such institutional scenarios.

One high-level thought I have is that in practice even in the current system most companies are not very profitable, in fact many of them (even big ones) don't even make consistently positive profits! In practice, employees (through insider knowledge and power, plus a competitive labor market) and customers (through competition for products) often get a large share of the gains and shareholders aren't left with a lot. I think the luxury of "should I maximize profits, after having made sure to be in a position of making consistent profits?" is probably faced by very few businesses, so I don't know what the practical import would be even if companies adopted your maxim.

I still like the spirit of your idea though!